| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

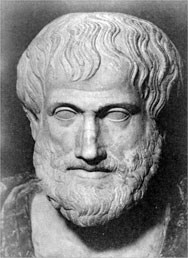

Aristotle, 384 - 322 B.C.E.

Ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, was born in Stagira, on the Chalcidice peninsula in the northwestern part of the Aegean Sea. His father had been a physician in the court of Amyntas II of Macedon. Upon his father's death, Aristotle was raised by relatives at Atarneus (on the Aeolian coast of Asia Minor). In 367 BCE, at the age of seventeen, Aristotle found his way to Athens and studied in Plato's Academy. Aristotle was to remain at the Athenian Academy for the next two decades. Ineligible for citizenship, Aristotle would remain a metic (resident alien) in Athens.

After Plato's death in 348, leadership of the Academy passed to Plato's nephew Speusippus. Perhaps disappointed he was passed over, and finding the xenophobic atmosphere in the city increasingly hostile to Macedonians and northern Greeks like himself, Aristotle left Athens around 347. Traveling to Asia Minor, Aristotle arrived in Atarneus at the invitation of the local ruler, Xernias. He was accompanied by his colleague Xenocrates, and soon joined by older colleagues Erastus and Coriscus. After a brief time at Xernias's court, they were given land at Assos to form a new school there. However, only four years later (for reasons unknown), Aristotle moved to the island of Lesbos and founded a new school at Mytilene.

In 342, king Philip of Macedon invited Aristotle to Pella, to serve as a tutor of his thirteen-year-old son, Alexander (later, the Great). But this engagement was also cut short three years later, when the young Alexander came to power and was too busy for tutors. Aristotle returned to his birthplace in Stagira (which had been lavishly reconstructed by Alexander) but was soon bored.

Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 and taught at a gymnasium called the Lyceum for the next decade. Aristotle's students and followers in Athens were known as the Peripatetics (for Aristotle's habit of walking as he lectured). .This was probably the most productive period of his life. Aristotle is estimated to have researched and written about 150 works during this period. The range of topics was vast, but Aristotle seemed to approach them all in the same systematic way. Reflecting his background as a physician's son, who had trained in biology, Aristotle took to grasping entire fields of knowledge, and breaking their concepts down into categories and classifying them taxonomically. Beyond his comprehensive treatment of topics, Aristotle also set forth his own detailed theories, and laid down the questions to be asked and the manner in which to answer them.

Aristotle's approach to "philosophy" (meaning knowledge in general) is often contrasted against that of his old teacher Plato. Roughly speaking, Plato had tended to be an idealist, believed the material world deceptive, and that the origin of ideas emanated from some higher metaphysical realm, that pure ideas, or "forms", existed somewhere above the world, that could only be accessed by reason. Aristotle was much more empirical, and believed ideas were merely human abstractions derived from real world observations.

For economists, Aristotle's most significant work are his Politics and Ethics, which contain his most important insights for social science. His Economics, by contrast, is little more than a handbook of household or estate management, and perhaps less useful. His starting point on social science is his conception of human society as a natural organism. Aristotle is often contrasted to the Sophists, a school of thought which believed in a disjuncture between human nature and human civilization (culture, laws, etc.), and that virtue could only be achieved by discarding the trappings of civilization and following the "natural". Aristotle starts of his Politics with a denial of that dichotomy, asserting that man is designed by nature to live in civilized social units, yielding his famous dictum "man is by nature a political animal". He gives a conjectural history of the formation and evolution of political units, from the family household, to the village, to its ultimate expression, the Greek polis or city-state.

His Politics are, in fact, a theoretical postscript or summary, of a research project undertaken by himself and his students examining the political constitutions of some 158 Greek city-states (only one of the research reports - on the Athenian constitution - survives). Unlike Plato, who conjectured about an ideal republic abstractly before proposing how to implement it in practice, Aristotle drew from existing political structures to find what worked and what did not work. The perennial taxonomist, Aristotle identified three types of constitutions - Monarchy, Aristocracy and "Polity", which in their corrupted form, show up as Tyranny, Oligarchy and Democracy. He believes that states should be ruled according to the idea of the good, which he identifies as the flourishing of virtue among its citizens. He identifies virtue as living a life according to reason, or ethics. Ever the philosopher of the golden mean, Aristotle warns against extreme types, and is suspicious of utopian schemes. He does not believe the political structure has to be perfect, but only approach the goal of virtue in this world. He does not impose a single formula - acknowledging that different political structures might fit different "temperaments" of peoples. Nonetheless, roughly speaking he sees the better societies are those governed by educated, adult free men of some economic means (and thus leisure to reflect). Women and slaves, he asserts, lack ratiocinative faculties, they are naturally incapable of reason, and thus require to be directed. Whereas the poorer classes, being economically desperate, are prone to corruption, and likely to rule according to their factional class interest rather than for the good of the polis. Aristotle writes extensively on the impact of wealth in society, and the dangers of excessive wealth inequality as both a corrupting and destabilizing factor. He believes in active government schemes to reduce inequality and undertaking other activities, such as provision of public education.

Upon the sudden death of Alexander the Great in 323, Aristotle realized that his close connection to the Macedonian monarchs would him a prime target for vengeful Athenians who had chafed under Macedonian rule. Predictably enough, Aristotle was indicted for impiety. But unlike his predecessor, Socrates, he decided not to appear before the Athenian tribunal. Instead, Aristotle and his family slipped out of Athens and made their way to exile in Chalcis (in Euoboea) where he died soon after.

Aristotle appointed Theophrastus as his successor in the leadership of the Lyceum, and entrusted him with his writings (essentially Aristotle's notes from his Lyceum lectures) Aristotle's teachings were carried on in Athens by the Peripatetic School, which remained active for centuries, although Aristotle's writings remained in limited circulation, and were at one point reputed lost. It is only really after 60 BCE when Peripatetic leader Andronicus of Rhodes put out a new edition of Aristotle's works, that they became accessible to the rest of the Graeco-Roman world.

In 529 CE, the Emperor Justinian shut down the Platonic Academy of Athens, feeling the pagan philosophy to be a threat to the new Christian order of the Byzantine Empire. The academics were scattered, many to the borderlands of Persia, and the memory of Aristotle's works was clandestinely preserved only by a few scholars. When the Abbasid Caliphate set up the School of Wisdom in Baghdad in the late 9th Century, Aristotle's works were resurrected from obscurity and translated by Muslim scholars.

The bulk of Aristotle's works were lost to western (Latin) Europe during the Dark Ages, during which time Aristotle was thought to have been merely a logician. This was based on the availability of only two of Aristotle's works, the Categories and Interpretation, as translated by Boethius, a 6th C. Roman in Ostrogoth Italy. Both were standard texts in Latin schools for several centuries. The neo-Aristotlean 'Nominalist' or 'Conceptualist' position during the early Medieval Scholastic debates were based largely on these two works plus Porphry's Introduction, a prelude to Aristotle's Categories composed in the 3rd CE. The rediscovery of the remainder of Aristotle's works in the Latin west would have to wait until the 12th Century.

Around 1120, the remainder of Boethius's translations of Aristotle's logical works (Prior Analytics, Topics and Sophistical Refutations), began to be found. In the 1140s, James of Venice, an Italian in Constantinople encountering the Aristotlean revival in the East, completed the logical organon by translating Posterior Analytics and possibly re-translating the pieces Boethius had already done James went on to breach other parts of Aristotle's philosophical opus for the first time, translating Physics, Metaphysics (up to Bk. IV), De Anima and the bulk of the Parva Naturalia collection. The Italian monk Burgundio de Pisa, for instance, translated works of Christian Neo-Platonists like Gregory of Nyssa and St. John Damascene, which paraphrased a lot of Aristotle's philosophy. Around the turn of the century, there emerged a manuscript known as Ethica Vetus, a Latin translation of Books II and III and Aristotle's Ethics. In 1240, the "middle commentary" (known as Liber Nicomachae) by Ibn Rushd (Averroes) was translated by Herman the German. Finally, in 1246-47, Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, translated the Nichomachean Ethics whole. The Politics and his other works followed not long after.

The translations of Aristotle and his commentators prompted the explosion of Medieval Scholasticism, spearheaded by Albertus Magnus and his student Thomas Aquinas, who worked a merger of Aristotlean philosophy and Christian theology. Aristotle was catapulted to cultish new heights, feted by the Scholastics as the supreme authority about everything. That reign continued virtually unbroken until the Renaissance humanists and early scientists began chipping away at the Aristotelian edifice

|

Major Works of Aristotle

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Aristotle

|

All rights reserved, Gonšalo L. Fonseca