| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

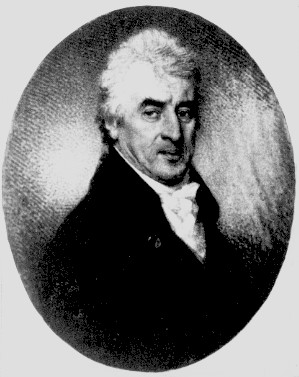

Arthur Young, 1741-1820

English farmer, journalist and agricultural economist.

Arthur Young was born the son of a clergyman, the rector of Bradfield, near Bury St. Edmunds in rural Suffolk, to a well-connected political family. After a period of schooling in Lavenham, young Arthur was apprenticed to a wine merchant in Lynn and groomed for a career in commerce. He showed an early aptitude for literary career, publishing a couple of political tracts on the Seven Years' War and novels while still in his teens.

After his father's death and at his mother's urging, Arthur Young, moved back to his family estates at Bradfield, near Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk, and tried his hand at farming. In 1767, Young moved on to Hertfordshire to set up his own farm. It was around this time that Young got interested in the new methods of farming to increase yields.

As one of his biographers quips, Young's writings "produced more private losses and more public benefit than those of any other author" (p.190)

Starting in late 1764, Arthur Young began publishing articles on farming in the Museum Rusticum et Commerciale, a short-lived journal of the time. These were republished and expanded in his Farmer's Letters (1767). Young became a proponent of the "scientific" agriculture, advertising new methods such as crop rotation, nitrogen-fixing, new implements, selective breeding, etc. He gathered much of what he learnt from his travels around England (his observations were duly reported in his 1768-1771 publications). He combined his enthusiasm for these novel techniques with more general observations about farm management, urging the landed gentry of England to become more "commerce-minded" about their estates. His 1774 Political Arithmetic was an attempt at a more general economic treatise.

Paradoxically, Young was himself never quite a success at farming and so, to supplement his income, he became a journalist for the Morning Post in 1773, reporting on Parliamentary debates. Yet that did not stop his promotion of agrarian innovation. His works were widely translated and his fame such that he was dispensing farming advice to such figures as the American president George Washington and the British King George III.

In 1780, Young published his Tour of Ireland, similar to his earlier English tours, but, this time, also an indictment of government policy. He denounced the Catholic penal laws and British commercial restrictions that kept Irish agriculture in a penurious state. In 1784, Young founded the Annals of Agriculture, a journal for like-minded agricultural reformers like himself (and others besides -- Jeremy Bentham published many of his papers here; so did "farmer" George III). In 1788-1790, Young happened to be traveling through France and observed the French Revolution first-hand. In his 1792 travelogue, Young identified how the dismal condition of French agriculture had made the Ancien regime unsustainable. His work speaks ominously of rural violence brought about by unemployment, absenteeism, and the concentration of property-ownership -- lessons, he thought, Britain ought to heed.

In 1793, Young was appointed secretary to the British Board of Agriculture under Sir John Sinclair, a new government institution designed to promote "scientific agriculture". Under Sinclair and Young, the Board conducted a series of extensive surveys of English counties..

Arthur Young's legacy is mixed. Certainly, his extensive travelogues and surveys have left economic historians with a lot of invaluable data. But the extent to which he was actually responsible (or involved) in the "Agricultural Revolution" in England is a bit more debatable. Many of the recommendations he made were suspect or outright folly. For all his careful county-by-county accounts, Young was apt to be so enthralled by any new method or institution to recommend its application across Britain, often with little regard for local differences in soil, climate and economy. Indeed, some have claimed that the agricultural revolution happened in spite of, rather than because of, Arthur Young. Young was first and foremost a journalist, not a farmer-scientist of the caliber of James Anderson. But it is precisely as a chronicler of the Agricultural Revolution that Young is most valuable.

|

Major Works of Arthur Young

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Arthur Young Contemporary

Modern

|

All rights reserved, Gonšalo L. Fonseca