| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

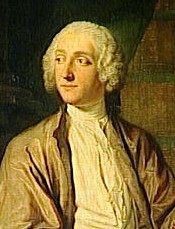

Victor Riqueti, Marquis de Mirabeau, 1715-1789.

French aristocrat and early leader of the Physiocratic sect.

Victor Riquetti, Marquis de Mirabeau, was an aspiring statesman, bubbling over in the Enlightenment spirit, a "feudal character invaded by democratic ideas", as de Tocqueville would characterize him. Mirabeau's first treatise (1750) called for the decentralization of the tax system across France so that the central government could simply make a lump sum demand for revenues from a province, and leave it up to provincial authorities to raise them as they saw fit. Such a system was indeed in place in the frontier provinces of France -- the so-called Pays d'État -- but in most other provinces -- the Pays d'Élection -- it was the royal representative (the intendant) who had to decide how to allocate the tax burdens. What Mirabeau called for was simply the elimination of the latter system and the extension of the former to all of France.

Mirabeau had long been in possession of a manuscript version of Richard Cantillon's Essai from which he drew many of his ideas and contemplated publishing it under his own name. In the end, he decided against it. Instead, he had Cantillon's essay published in 1755 and decided to compose a separate series of commentaries on it. These came out in 1756, under the signature of L'Ami des Hommes -- the "Friend of Mankind" -- an appellation by which Mirabeau became known (often derisorily) for the remainder of his life (he would sign many of his works simply as L.D.H.)

In his commentaries, Mirabeau seems to have misinterpeted the wage-fertility dynamics of Cantillon's theory. He was left with the impression that "population" was the measure of a nation's wealth and policy should be geared to maximizing population growth. To this end, Mirabeau argued for loosening restrictions on grain imports in order to lower food prices. He also recommended the promotion of small peasant-proprietorship in land, which he believed would encourage stabler livelihoods and thus larger families among the peasantry, as well as avoid the unproductiveness of "absentee ownership", so prevalent with large farms. The book was, to say the least, a sensation, going through multiple editions, and the "Friend of Mankind" was discussed in every salon.

Intrigued, the wizened court physician, François Quesnay, summoned the "Friend of Mankind" to a meeting in July 1757 at his entresol in Versailles to "set him right" on these points. Quesnay relayed to Mirabeau the economic doctrine he was himself developing and the points of contact between their theories. Population, Quesnay insisted, was the effect, not the cause, of wealth. The wealth of a nation is the "net product" of its agricultural sector and this is best achieved by higher grain prices (i.e. discouraging imports) and agricultural efficiency is best served by economies of scale (i.e. large farms). In that celebrated evening, Mirabeau was won over completely. He became the first disciple of Quesnay and the most faithful of what would later be known as the "Physiocratic" sect.

A man of action more than thought, Mirabeau set it upon himself to popularize Quesnay's theory and recruit new members into the sect. Most of the wide public became first acquainted with Quesnay's Tableau through its reproduction in the 'Continuation of Part 6' (1760) of Mirabeau's L'ami des hommes.

[Note: The original 1756 l'ami des hommes consisted of three parts - the first on population and agriculture, the second on commerce and industry, the third on foreign trade and colonies. Mirabeau would append further writings between 1758 and 1760, bringing the total work up to eight parts. The Tableau came out as the 'continuation' of the sixth part (thus sometimes just labeled the seventh part).]

Mirabeau was the primary architect of the Physiocrats' "single tax" doctrine, expounded in his 1760 théorie de l'impôt. This was a controversial book. France was then in the process of losing what was left of its empire in the Seven-Years War. To finance this, the Crown was wringing the country dry with an incredibly inept tax system, in which an estimated 2/3rds of the potential tax revenues were lost to private middlemen. Interestingly, Mirabeau defended the tax exemptions enjoyed by the nobility in return for their public service as officers, judges, etc. He believed this was better than abolishing the exemptions and using the tax revenues to hire a professional bureaucracy. At least the exemption system put idle noblemen "to work", while the latter system would draw productive citizens away from useful activities like farming, manufacturing and commerce. Besides, he speculated, professionalization of State office almost always meant corruption and inefficiency -- he held up the terrible results of private tax-farming to illustrate his point.

Mirabeau bravely challenged not only the insanity and brutality of the French fiscal system, but also the very policy priorities of the French Crown. In his outlandish prose, Mirabeau openly questioned the monarch's right to an empire, given his inability to govern well at home. Clearly, by directly insulting King Louis XV, he had stepped over the line -- and the Madame de Pompadour could not protect him now. As could be expected, Mirabeau was hauled off to jail at Vincennes in December 1760. Through Pompadour's intercession, Mirabeau was released, but warned to stay confined to his rural estates in Bignon and refrain from writing again.

Mirabeau remained quiet until the sudden appearance of the young DuPont de Nemours' treatise calling for fiscal reform along Physiocratic lines. As the authorities had let this circulate, Mirabeau reasoned, he ought to venture returning to print. That same year, Mirabeau published his soft-spoken Philosophie rurale, incorporating some of Quesnay's own work. This has been considered the best statement of early Physiocratic doctrine.

Riding on the coat-tails of his new celebrity, Mirabeau decided to expand the Physiocratic message out of the halls of Versailles and into Paris society. Mirabeau's Paris home became the public headquarters of the Physiocratic sect -- which met, every Tuesday, for dinner and discussion (the reclusive Quesnay did not attend, but the conversations were relayed to him).

As a curious aside, we should note Mirabeau's role in the "cheap mills" movement. Soon after the famine of 1767 and prodded by Baudeau, Mirabeau set up a cheap flour-mill and bakery upon his estate in Fleury and produced excellent bread which he sold to the population at two-thirds of the going price. He made a pretty penny and "proved" the ridiculousness of feudal restriction of banalité (which required peasants to grind their flour in their lord's mill). Mirabeau's "cheap mill" example was much followed by other "enlightened" noblemen.

It was Mirabeau, more than anybody else, who is responsible for the curious reputation of the Physiocrats as a sect of mystical charlatans and insufferable sycophants. His bold, unrestrained, flowery and half-reasoned rhetoric irked many about him. Indeed, some have speculated that not only would Mirabeau have avoided his arrest but might actually have succeeded in furthering serious economic reforms, had he only used a milder and more sensible way of expressing himself. More than once, Voltaire used his sharp wit to poke fun at Mirabeau (whom he detested more at a personal than an intellectual level).

The latter part of Mirabeau's life was enveloped in public scandal. The "Friend of Mankind" had, apparently, been using the very instruments of aristocratic privilege, to persecute his unruly wife and rebellious children. Mirabeau died on July 13th, 1789 -- the eve of the storming of the Bastille. He is also known as "Mirabeau the Elder" to distinguish him from his estranged son, Gabriel Honoré Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau ('Mirabeau the Younger'), the great orator of the National Assembly during the French Revolution.

|

Major Works of Victor de Mirabeau

|

HET

|

|

Resources on the Marquis de Mirabeau

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca