| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

Antoine de Montchrétien, 1575-1621.

Easily one of the more colorful figures in the history of economics, Antoine de Montchrétien (or Montchréstien), Seigneur de Vasteville, was a French Mercantilist thinker - and dramatist, poet, duellist, hardware manufacturer, governor, arriviste nobleman and soldier of fortune - credited for originating the term "political economy".

Born a commoner, the son of apothecarist, in Falaise (Normandy), Antoine de Montchrétien was orphaned early and taken under the wing of a local French nobleman, François Thésart, Seigneur des Essarts. This allowed him to acquire a decent education at the schools of Caen, including in the noble arts of riding and swordmanship.

Around the turn of the century, Montchrétien emerged as a famous poet and dramatist, commonly associated with the fashionable Pléiade style. He was the author classical tragedies of the French dramatic canon like La Cartaginoise (1596), L'Ecossaise (1601), Hector (1604), with emphasis on elaborate lyrical choruses. Throughout this period, he lived the stormy life of an artist, conjoined with the rascally persona of a quarrelsome young noble, engaging in continuous duels with his cohort. However, he also engaged in some serious reading, having authored a history of Normandy (unpublished) during this time.

In 1605, Montchrétien killed an adversary in a duel, and fearing the law (duels had been recently outlawed), fled to England. It is there that he became an economist. His interest had been sparked by the spectacle of the exiled French Huguenot community, who were heavily engaged in the crafts industries and commerce in London. He began reflecting on the price the religious quarrels in France had exacted on her productive power and prosperity. The Elizabethan attention on nurturing and protecting commerce and national industry also attracted his attention.

Montchrétien returned to France around 1610, (his return facilitated by the intervention of James I of England, who was a fan of his plays), convinced by the lessons he learnt in England. He swiftly married a wealthy Norman widow, who helped him set up a steel foundry and hardware workshop (knives, principally) in Ousonne-sur-Loire and rent a warehouse in Paris, his principal market.

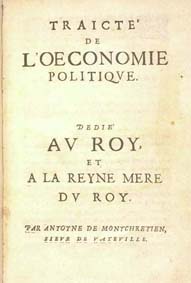

It was during this time that he set down to write his Traité de l'oeconomie politique (1615). Besides coining the title of the new science, the Traité is also renowned for being one of the most articulate and subtle of Mercantilist tracts. Montchrétien's thesis is presented as a plea to King Louis XIII and his mother, the regent-queen Marie de Medici, to protect the commerce and elevate the national industries of France. Drawing loosely from his English observations and works of Jean Bodin, lays out a keen, articulate case, laying out the central features of mature Mercantilism, anticipating Thomas Mun by several years.

Montchrétien's Traité was well-received by Guillaume de Vair (keeper of the seals, i.e. minister of justice), who afforded him entry into the counsel of Louis XIII in 1617. But it is probable that his advice proved irritating, as later that same year, we find Montchrétien appointed governor of Châtillon-sur-Loire and ennobled with the title of "Seigneur de Vasteville", conveniently getting him out of earshot of the monarch.

The outbreak of Huguenot uprising of 1621 proved fatal. Although Montchrétien was probably Catholic by faith (at least, there is no evidence otherwise), he nonetheless took up the side of the rebellion. Why he did so is not particularly clear. Nonetheless, Montchrétien strapped on his sword and set about raising armies in the Maine region and Lower Normandy, marching them in relief of the embattled Huguenot citadels. But in October, 1621, at a hostelry near Tourailles, Montchrétien was ambushed and killed by Claude Turgot, Seigneur des Tourailles (of the same ancestral house that would later produce the great Jacques Turgot). Deprived of a live rebel, the court at Domfort put Montchrétien's cadaver on makeshift trial, sentencing his bones to be smashed with iron, his corpse burnt and his ashes scattered.

After his death, Montchrétien's name fell into obscurity. His reputation was savaged by contemporaries, and slanderous allegations circulating accusing the rebel of being an apostate, a forger, a highwayman, and a myriad of other likely falsehoods. Montchrétien's fallen reputation may help explain why his Traité was not as appreciated and influential upon later French economists as it probably should have been.

|

Major Works of Antoine de Montchrétien

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Antoine de Montchretien

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca