| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

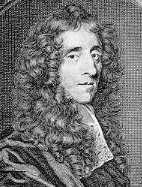

John Locke, 1632-1704.

Prominent empiricist philosopher, natural law social thinker and Whig political theorist, John Locke was nonetheless a rather traditional Mercantilist in his economics.

John Locke was born in Wrington (near Bristol), to a family of petty gentry of Puritan religious convictions. His father had served as a captain in the parliamentary army during the English Civil War of the 1640s. and subsequently became a lawyer and jurisconsult for local Somerset magistrates. After finishing school at Westminster, John Locke enrolled at Christ Church College, Oxford in 1652, where he would remain for the next fifteen years. Locke studied classics, philosophy and medicine, earning his B.A. in 1656 and his MA in 1659. Although he had been a quiet, unremarkable student, Locke was nonetheless appointed lecturer in Greek at Christ Church from 1660. A special royal dispensation from Charles II allowed Locke to stay on at Oxford beyond the prescribed terms without ordination. In 1663, Locke was elected censor in natural philosophy. Locke acquired a passion for medicine, and studied it independently from 1658. Through it, he came into the circle of the chemistry pioneer Robert Boyle, and his clique of "experimental" scientists at Oxford. Although he was initially denied a degree in medicine at Oxford, Locke nonetheless made something of a name for himself as a physician, and would eventually be elected to the Royal Society in 1668.

Locke's future path was changed by his fateful meeting in June, 1666 with Anthony Ashley Cooper (future Earl of Shaftesbury, Whig political leader and grandfather of the utilitarian). Ashley had come to Oxford to seek a water cure for a liver ailment, and was struck by Locke, and hired him on the spot as his personal physician (Locke would go on to perform a novel surgical procedure on Ashley's liver that apparently cured the ailment). From 1667, Locke lived in Ashley's household at Exeter House on the Strand in London. Ashley was, at this time, at the height of his political power. As the powerful chancellor of the exchequer, Ashley formed part of the small clique (known as "the Cabal") that dominated the government under King Charles II of Great Britain. Ashley was a proprietor of Carolina Colony in America and an ardent Mercantilist, ready to promote any cause that furthered England's trading interests. Seeing the Dutch Republic as England's greatest threat, Ashley made a famous war-mongering speech in parliament, comparing England to Rome and Holland to Carthage (and "Delenda Carthago est"). Ashley reached his peak in 1672, when he was granted the title of first Earl of Shaftesbury and raised to first lord of trade and lord chancellor of England.

Although Locke was primarily Ashley-Shaftesbury's physician, he imbibed the political atmosphere of the Shaftesbury home, and soon became his secretary and informal advisor. Locke authored several unpublished political memoranda for Ashley-Shaftesbury, notably his Essay on Toleration (1667) and his Constitution for Carolina (1669). Around 1668, John Locke also authored his first economics piece, a memo to Shaftesbury on Sir Josiah Child's recent 1668 proposal to lower the interest rate from 6 to 4 percent. Although unpublished, the memo would form the basis for Locke's later economic works. Locke also got deeply involved in the practical issues of commerce and colonial development. When Shaftesbury combined the boards of commerce and colonies under his presidency, Locke was appointed as secretary to the Council of Trade and Plantations. That same year, Locke joined Shaftesbury as one of the eleven investors in the "Company of Adventurers to Bahamas", proprietors of the English colony of the Bahamas (which included several slave plantations).

Along with the rest of the Cabal, Shaftesbury fell from power in late 1673. But he soon re-emerged in the House of Lords as the leader of the Whig opposition to the Crown. With his patron now an outsider, Locke's days were numbered. When the Council of Trade and Plantations was split up in 1675, Locke resigned his position and returned to Oxford. This time around, Locke secured his BA in medicine and a license to practice medicine. But he did not stay in Oxford for long, and, in the capacity of a tutor, went abroad to France for three years.

After several years of political tussle, Charles II brought Shaftesbury back into the Privy Council in 1679, in the hopes that might tame him. But Shaftesbury insisted on spearheading the parliamentary effort to exclude Charles II's brother James, Duke of York, from the succession to the throne on account of James being a Roman Catholic. Shaftesbury and the Whigs demanded that Charles II raise up his illegitimate Protestant son, James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, as the new heir to the throne. Having returned from France in 1679, Locke re-connected with Shaftesbury, but with the "exclusion bill" crisis at its height, Locke wisely realized he ought to keep his distance from the political fray. Locke remained quietly at Oxford, apparently aloof from afar, but in reality was knee-deep involved in providing the arguments for Shaftesbury's political challenge to the crown. It is believed that Locke composed his Two Treatises on Government during this time. His first treatise, written c.1681, addressed the "divine right of kings" argument that had recently been promoted in a book by Sir Robert Filmer. His more famous second treatise, composed either in 1679 or 1683 (historians are divided), articulated Locke's famous thesis on natural law, property and government by consent. Neither treatise was published at the time. In 1681, Shaftesbury was arrested and charged with treason. Although acquitted at his trial, Shaftesbury promptly went into exile into Holland. Locke had kept enough distance to not be dragged into it. But a couple of years later, in 1683, several prominent Whigs were implicated in the Rye House Plot to place Monmouth on the throne by force. While it is unclear that such a plot even existed, the crown nonetheless used it to persecute opponents. Locke realized he was under suspicion, and decided it was time to go. Locke fled to Holland in 1683, where he would remain under an assumed name for the next six years.

Politically wary, John Locke was never very keen to publish his ideas, or sign his name to them. It was only in the late 1680s, when he was already in his fifties, that Locke published his first works in Jean le Clerc's Bibliothèque universelle. It included Locke's reviews of Boyle's medical treatise (1686) and Newton's Principia (1688) (and some others which cannot be certainly attributed). Of his original compositions, Locke published an article on commonplace books (1688), and an abridged first draft of his essay on human understanding.(1688).

In late 1688, the Dutch prince William of Orange invaded England, and the Stuart monarch James II fled to France. In February 1689, the British parliament declared the throne vacant and acclaimed William and his English wife as king William III and Mary II of Great Britain. At their coronation, William and Mary were read a "Bill of Rights" drafted by Parliament, and subsequently passed into law, effectively establishing England as a constitutional monarchy. Locke left Holland and arrived in England on the same boat that carried Mary II - and brought along piles of manuscripts he had been writing during his exile.

Locke's Letter on Toleration, defending religious toleration, appeared in late 1689. The letter had been originally written in 1685, in the aftermath of the French king's revocation of the Edict of Nantes (withdrawing toleration from Protestant Huguenots), and draws on many of the arguments first outlined by Locke back in his 1667 essay. Locke had originally written his new letter in Latin to a Dutch friend, who had it published (without Locke's permission) in Gouda, Holland in early 1689. There were French and Dutch translations before an unauthorized English translation (by the Unitarian merchant William Popple) appeared later in the fall of 1689 (after parliament had already passed the act of toleration). In his original 1667 essay, Locke had argued that intolerance was unreasonable as government policy - the nature of human belief is such that a person cannot really control his own beliefs, much less an outsider compelling his belief by force, even if they manage to achieve outward compliance. Moreover, it falls outside the scope of government magistrates, whose sole mandate is to ensure the peace. His 1689 Letter goes beyond government policy to address tolerance by people in general for other people. Echoing his new ideas of a voluntary social commonwealth, Locke asserts that men do not enter into civil society in order to save their souls or have their beliefs designated by others. And if that responsibility is not assigned to civil society, then it is not assigned to magistrates. Moreover, even if it was possible to compel belief by force (which it is not, be assuming it is), it would nonetheless be an evil, and detrimental to the very religion one is trying to promote. If it is right for the English State to impose the "true" Christian religion on people of different sects or faiths, then generalizing, it is no less right for the French state to impose Catholicism, or Muslim states to impose Islam, in theirs. Religion would be diminished to an accident of the country of birth and not conviction, and would be detrimental to the advance of "true" Christianity. Locke goes on to explain how magistrates are human and have no competence on religion, that churches are and should be regarded as voluntary associations, and that even apparently minor impositions, such as forcing as High Church ceremonies on Low Church sects, are outside his jurisdiction. Compelling men to act even outwardly against their judgment and sincere beliefs is an evil in itself. Outward compliance only works on the irreligious who don't care either way, and fills the church with hypocrites, while causing pointless suffering to sincere believers. Locke allows exceptions where intolerance may be justified - e.g. if following a particular religious sect has civil consequences, like any ordinary crime e.g. if religious adherence requires allegiance to foreign powers, or the overthrow of the government (clearly here Locke has Roman Catholics in mind). Locke's letter provoked a critique from the High Church Anglican minister Jonas Proast of Oxford. Proast agreed that compulsion of belief was silly, but "moderate" force may nonetheless be a useful tool to "inform" those who would otherwise never come across the "true" religion. Locke replied with his Second Letter (1690). Proast responded with a Third Letter in 1691, prompting Locke to write his own massive Third Letter (1692). A dozen years would pass before Proast published his reply to Locke (confusingly called Second Letter in 1704), to which Locke drafted a rejoinder in his Fourth Letter (1704, unfinished).

Locke also published (albeit anonymously) his Two Treatises on Government in 1690.. It was a pathbreaking classic of natural law and political philosophy. It had its roots partly in Locke's theological meanderings, partly in his political Whiggery during the exclusion crisis. At its center is Locke's theory of property, namely, that property rights are determined by labor ("workmanship"). Locke considers it self-evident that every man has property rights over his own labor, and by extension property rights over what his labor produces. This is mirrored in the Divine, that all men are created by God, and belong to God (not to other men), and that the earth and its resources was created by God not for the kings or the few, but for the common benefit of mankind. Contrary to Hobbes, Locke starts on an assumption that abundance and peace was the state of nature, rather than scarcity and conflict. As a result, property rights emerged from the fact of labor (Locke uses the famous analogy of how water in the well belongs to all, but the water in the bucket belongs to him who drew it). He goes on to describe the political commonwealth as a deliberate and conscious creation of men, that men enter into agreements with each other it in order to protect their property rights. In this respect, he echoes Hobbes - although where Hobbes thought coming under the Leviathan was merely a rational necessity, Locke asserts it was an empirical fact, that such social contracts were made historically. This leads him to the conclusion that government, being created by men, is owned by the men who constitute civil society. Consequently, the legitimacy of a government, rests on consent of the governed, the extent to which civil society feels it is fulfilling its role, protecting individual and property rights, and retain civil rights to resist tyranny. Although Locke's treatise is not quite articulating popular sovereignty, it comes quite close.

Locke also emphasizes the vital importance of the separation of powers to keep tyranny at bay. He enunciates the three political powers as legislative (making laws), executive (executing laws) and federative (military defense). He does not include the judiciary as a separate branch (that would have to wait until Montesequieu). Although Locke allows that the executive and the federative might be usefully conducted by the same branch, he is adamant about the importance of separating the legislative from the executive. Thus Locke's 1690 Two Treatises seemed to many to provide the philosophical underpinnings of the 1688 Glorious Revolution.

Then came the Essay on Human Understanding, the only treatise Locke signed his name to. Although Locke began planning it as early as 1671, he only began actually writing it around 1687, during his stay in Holland (an early draft made it into the Bibliotheque Universelle in 1688). His time in Holland had been spent in consultation and debate with local philosophers and theologians, and it was there that Locke became better acquainted with continental European philosophy, notably the rationalist epistemology of Descartes and Spinoza. The full Essay concerning Human Understanding finally appeared in 1690. In it, Locke articulated an empiricist epistemology, denying the possibility of innate ideas (as the rationalists had argued). Man, Locke famously asserted, was born a "blank slate", and his ideas of the world came primarily from his senses. Locke's empiricist school of British philosophy would be followed up by George Berkeley and David Hume.

Sir Josiah Child's proposal to lower the rate of interest from 6% to 4% came up again. The bill was introduced into parliament in November 1691. Locke dusted off his old memos and hurriedly published his Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest, in opposition to it. It had only partial effect - parliament split the difference and agreed to lower it to 5%. Locke's pamphlet also asked parliament to consider the problems of the state of silver coinage in England. English coinage had been steadily deteriorating for the past half century. Because they legally circulated at face value, bad coins (clipped, underweight hammered coins) were the only coins that circulated internally, while good coins (full-weight milled coins) were removed from circulation (either hoarded, melted down or exported abroad). Locke urged parliament to consider reminting the coinage of the realm, and, in the interim, to adjust the law to allow bad coins to circulate by intrinsic metal content. His pleas had no effect at the time.

In 1694-95, at the height of the French wars, a sudden crisis of confidence gripped English money-holders, which led to an upsurge in hoarding of good silver and a flight to the gold guinea. This provoked a tumble in the value of banknotes of the fledgling Bank of England (f.1694) and a brief recession. In early 1695, parliament appointed a commission, headed by William Lowndes, to look into the currency problem. Lowndes' Report recommended reminting to entire coinage of the realm. But to ease the pain of adjustment (and lighten the government's debt burden), Lowndes also recommended a simultaneous devaluation of the pound - a general depreciation of 25% and the raising the face value of coins. Locke responded immediately with his Further Considerations (1695). It approved reminting, but denounced Lowndes devaluation scheme, arguing again for the restoration of the old coinage to their intrinsic value to ensure confidence of contract. Locke's argument persuaded the Whig minister Charles Montagu (future Earl of Halifax, then chancellor of the exchequer and a sponsor of the Bank of England). In November 1695, at Montagu's urging, parliament voted for Locke's scheme rather than Lowndes's. The entire English coinage was to be re-minted at the old intrinsic metal ratio. Some £7 million in silver money and £3 million in gold money will be reminted in the course of the next few years.

It in his first tract, Some Considerations (1691), where Locke develops his contributions to economic theory. Locke introduces the concept of "money as convention" as well as, following Bodin, the main elements of the Quantity Theory of Money, notably the concept of "velocity". Locke saw that the lowering of interest by legal means might very well lead to a collapse in trade because it would not reflect the "natural scarcity" of money. If money collapsed, then there would be, alternatively, a collapse in output or prices. The collapse in prices would lead to relatively cheap English goods and relatively expensive foreign ones "both which will keep us poor" (Locke, 1691). Unlike Mun, Locke did not see this as a promoter of exports.

Locke's ideas on value are a bit obtuse and inconsistent. In his 1690 Two Treatises, Locke proposes a quite explicit labor theory of value. But in his 1691 Some Considerations, Locke seems to adhere to a supply-and-demand-based theory of value. John Law (1705) did much to clarify the confusion between them.

Locke also proposed a theory of property in his 1690 Treatises. The right to property, Locke claims, is derived from the labor of those who work it. More specifically, he perceives that as "labor" is naturally "owned" by the person in whom it is embodied, then consequently anything that labor is applied to, is similarly "owned" by the laborer -- a rather proto-Marxian notion. Locke's "natural labor theory of property" stands in stark contrast to that of Hobbes, who conceived of property merely as a State guarantee, and of Grotius, who contended that property emerges from social consent.

Locke's ideas on money were in tandem to the English currency crisis of the early 1690s. For the past half-century, English money-holders had lived comfortably with deteriorated silver coins, but a sudden crisis of confidence related to poor harvests and the Nine-Years' War had led to a sudden flight away from silver and towards gold currency. The English gold guinea (nominally worth 20 silver shillings) was being traded on the open market at 30 shillings per guinea -- 50% above its face value. Notes from the fledgling Bank of England were being traded far below par. The government had concluded that the best route was to remedy the deteriorated state of silver coins and remint the entire coinage of the realm. The question was at what rate. The Secretary of the Treasury, William Lowndes, recommended a simultaneous devaluation of the pound sterling (to ease the pain and lighten the government's debt burden). But John Locke argued for reminting at the old intrinsic metal value in order to maintain "confidence" in debt contracts. With an eye on the foreign (i.e. Dutch) holders of English debt, Parliament ended up adopting Locke's program and, 1696, the entire English coinage was reminted at the old ratio at the extraordinary cost of nearly £7 million.

During this monetary reform, in an effort to stem the flight to gold, the value of the gold guinea had been increased from its earlier face value of 20 silver shillings to its new face value of 22 shillings -- thus the implicit mint ratio was readjusted to 1 unit of gold to 15.9 units silver. However, gold mining in Brazil had recently taken off, bringing the value of gold in terms of silver on the European market down to the ratio of 1:15. As the royal mint and market ratios were different, gold poured from Europe into England, while a reverse flow sent silver out. John Locke, who believed that silver (and not gold) was the "proper" metal for English currency ("let gold find its own value", as he put it) went into print again, this time pleading for a further devaluation of the guinea. Listening to Locke, the English authorities duly reduced the value of a gold guinea to 21s 6d. It was lowered once more by Newton a little later on. But the ratio was still too high. England would remain a gold magnet throughout the next century.

|

Major Works of John Locke

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on John Locke Contemporary

Modern

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca