| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

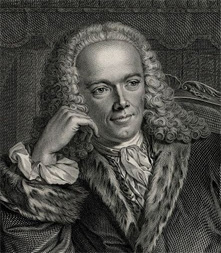

François Quesnay, 1694-1774.

The humbly-born François Quesnay, the son of a plowman, trained himself in medicine, rising to become a physician in Louis XV's court and the leader of a sect of Enlightenment thinkers known as the Physiocrats or the économistes. The working-class boy who could not read until he was 11 would be eventually elected to the Academy of Sciences and hailed as the "Confucius of Europe", the "modern Socrates", the "Moses of our day", by his gentlemen-disciples.

Born in Méré to a family of laborers, Quesnay was orphaned at thirteen. He learned to read from a household medical companion and quickly acquired a voracious appetite for more books and learning. In 1711, he began an apprenticeship to a Parisian engraver, while attending courses at the surgeon's college of Saint-Côme. After completing his apprenticeship in 1717, Quesnay married a Parisian grocer's daughter with a substantial dowry and set himself up as a barber-surgeon in Mantes, near Paris.

Quesnay's (rapid) self-education and skills shone through and, recommendation upon recommendation, he gradually climbed up the greasy pole. In 1734, the widowed Quesnay entered into the service of the household of Louis François de Neuville, Duke de Villeroy, powerful lord of the Lyonnais. This gave him some time to do more reading, studying and writing.

Quesnay cemented his reputation with his 1736 tract on surgery, prefaced by the separately-published Essai physique of much note. With this, he joined the struggle to elevate surgery (then a craft) to the status of a medical science (much to the academic medical establishment's horror). King Louis XV's edict of 1743 separating surgeons from barbers was in small part due to Quesnay's influential tracts. Interestingly, Quesnay had obtained a doctorate in medicine by then, but at Pont-á-Mousson rather than Paris.

It is around this time that François Le Peyronie, director of the newly-created Académie royale de chirurgie (royal college of surgeons), took up the role of mentor and sponsored Quesnay's appointment as its perpetual secretary. Quesnay's 1743 "Preface" to the Memoires of the Academie is interesting as a tentative venture into epistemology and philosophy of science, holding up surgery as the ideal combination of theory, observation and practice that should be followed in all sciences (he would draw upon it later for his "Evidence" article in the Encyclopedie).

In 1749, on the strength of a strong recommendation, Quesnay became the personal physician of Madame de Pompadour, the powerful mistress of King Louis XV and effective prime minister of France. Quesnay settled in Versailles, finally entering the highest circle of power. He was elected to both the Academié des Sciences and the Royal Society of London in 1751 and, the very next year, Quesnay received his letters of nobility. Quesnay purchased his survivance as first physician to the king with a loan from La Peyronie,

At Versailles, François Quesnay fell in with the philosophes, who curiously sought out the little country surgeon who had so bravely challenged the great doctors. Quesnay's apartment in the entresol of the palace of Versailles, became a meeting ground for many of the great Enlightenment philosophers. Diderot, d'Alembert, Helvetius, Turgot, Buffon and the Madame de Pompadour herself dined often in Quesnay's crowded rooms. Adam Smith, on his visit to France in 1766, spent several evenings there.

Quesnay's interest in economics arose in 1756, where, hoping to draw on his country background, he was asked to contribute several articles on farming to the Encylopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert. (three of Quesnay's articles - "Évidence", "Fermiers", "Grains" - were published in the Encylopèdie, four additional articles were drafted but withheld) In preparation for his articles, Quesnay delved into the works of the Maréchal de Vauban, Pierre de Boisguilbert, Claude Herbert, Dutot and Richard Cantillon and, mixing all these ingredients together, Quesnay gradually came up with his famous economic theory.

In 1758, Quesnay wrote his Tableau Économique -- renowned for its famous "zig-zag" depiction of income flows between economic sectors-- to explain his doctrine. It became the founding document of the Physiocratic system -- and the ancestor of the multisectoral input-output systems of Marx , Sraffa and Leontief and modern general equilibrium theory. (See our analysis of Quesnay's Tableau).

Quesnay began with the axiom that agriculture is the only source of produit net (net product, or surplus of output above cost). He believed that manufacturing and commerce were "sterile" as (in his view), the value of their output was equal to the value of their inputs. Only land, Quesnay reasoned, produced more than went into it. The wealth of a nation, Quesnay argued, lies in the size of its net product.

Quesnay opposed the mercantilist doctrines of Colbert, which still held sway in the French court, believing that they concentrated too much on propping up industry and commerce rather than agriculture. Influenced by Vincent de Gournay, an advocate of laissez-faire, Quesnay wished to see many of the Medieval rules governing agricultural production lifted, permitting the economy to find its "natural state". The natural state of the economy was conceived as the balanced circular flow of income between economic sectors and thus social classes which maximized the net product. In these concepts, Quesnay saw analogies to the circulation of human blood and the homeostasis of a body.

Quesnay was largely responsible for the distinction between the ordre naturel (nature's order) and the ordre positif (positive, i.e. human-idealized, order). A good government, Quesnay argued, should follow a laissez-faire policy so that the ordre naturel could emerge.

Cautious of his position in the royal palace, Quesnay did not publish his Tableau Economique under his name. Indeed a decade later, Dupont de Nemours in his Physiocratie merely notes that the "inventor the Tableau" was a "simple and modest man, who has never allowed himself to be named" (1767: p.lxxiii)

Quesnay had met the Marquis de Mirabeau in 1757 who quickly became his first full convert and the energetic founder of the Physiocratic "sect". Mirabeau was soon joined by Mercier de la Riviere, DuPont de Nemours and several others. Through the 1760s, the sect gathered at Quesnay's Versailles entresol but, unlike other visitors, they were not there for intellectual debate but rather to take down the words of the "master". They took it upon themselves to popularize the Physiocratic doctrine. It was the presentations, commentaries and elucidations upon Quesnay's system by Mirabeau (1760, 1763), Mercier de la Riviere (1767) and DuPont de Nemours (1767) that gave Quesnay's ideas a more systematic feel.

After a brief interlude, Quesnay had another splurge of activity, writing numerous articles on economics in the Physiocratic journals then under the control of Dupont. Quesnay's articles appeared in 1765-8 in the Journal de l'agriculture, du commerce et de finances and in the Ephémérides du Citoyen under pseudonyms like M.N., M.H., M.A., M. de Isles, etc. (sometimes having his alter-egos enjoin in journal debates with each other, esp. Mr. H questioning the doctrine, Mr. N defending it). Quesnay's 1766 formule article is perhaps his clearest presentation of his theory.

The Physiocratic sect's worship of Quesnay knew no bounds -- and, to some extent, this went to Quesnay's head. The increasingly senile Quesnay began believing that he was, indeed, the wisest man in the kingdom. Against the advice of d'Alembert, Turgot and other more cool-headed friends, Quesnay published in 1773 a mathematical book claiming to have uncovered new truths in geometry (including squaring the circle). It was pure rubbish and Quesnay's reputation suffered accordingly. "It's the scandal to end all scandals, the sun has lost its light", Turgot mumbled.

The death of the Madame de Pompadour in 1764 weakened the protection the Physiocrats had enjoyed in Court, but King Louis XV stuck faithfully by Quesnay himself. The affection was not reciprocated: Quesnay had little respect for the old pleasure-loving monarch, much preferring his grandson and heir. However, upon ascending to the throne in 1774, the new King Louis XVI, eager to make a clean start for his reign, expelled Quesnay from Versailles' entresol. Quesnay died later that same year.

|

Major works of François Quesnay

|

HET

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Resources on François Quesnay Contemporary

19th Century

Modern

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca