| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

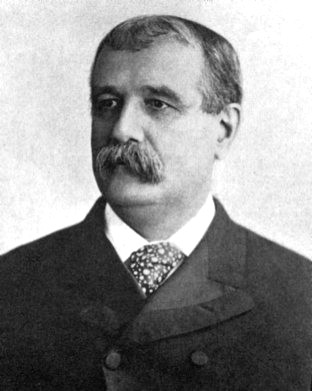

Gen. Francis Amasa Walker, 1840-1897.

Widely regarded as the "dean" of American economics. Francis Amasa Walker was born on June 2, 1840. His father, the economist Amasa Walker had settled in Amherst, Massachusetts where Walker was to get his early education. He acquired his B.A. from Amherst College in 1860 and joined a law firm. In 1862, when the American Civil War broke out, Francis Walker volunteered for the Union Army of the Potomac. His bravery and prowess earned him quick promotions and many wounds. He was captured by Confederate forces at Petersburg in 1864, but was returned later that year during a prisoner exchange. In 1865, while still twenty-four, he was brevetted brigadier general.

After the war, Walker returned to Amherst to teach Greek and Latin at Williston Seminary and Amherst College. He helped his father prepare his 1866 treatise Science of Wealth and fully absorbed his father's teachings in Classical economics However, bored by abstraction, Walker left for Washington DC in 1869 in the hopes of starting up a career in journalism. For a year, he worked under David A. Wells at the Bureau of Statistics at the Treasury. Walker did such an exceptional job that he was appointed superintendent of the tenth U.S. Census of 1870. He had just turned thirty.

Walker's unusually thorough collection, sifting and presentation of the census results (published in 1874 as the Statistical Atlas earned him a well-merited applause from statisticians and scholars everywhere. In 1871, he worked for a while as Commissioner for Indian Affairs in the Grant administration. In 1872, Walker was invited by Yale University to replace Daniel Coit Gilman at the Sheffield Scientific School. Walker was Yale's first professor of political economy.

Walker's stay at Yale, however, was not a very happy one. Without a Yale B.A. and confined to the Sheffield ghetto, Walker felt very much the outsider there. His rival at Yale College, the dogmatic conservative economist William Graham Sumner, had the ear of the administration. Sumner's abrasive personality grated on Walker. The statistically-minded Walker was kindly disposed towards the "New Generation" of German-trained American economists, whereas Sumner saw them as his enemies. Perhaps because of this, Walker did not pass up opportunities to absent himself from Yale. For a time (1877-79), Walker served as visiting professor at the fledgling the Johns Hopkins University, one of the returnees' citadels. In 1878, Walker was the US delegate to the international monetary conference in Paris, and subsequently accepted appointment as the superintendent of the 1880 census.

Francis A. Walker finally resigned from Yale in 1881 to become one of the first presidents of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), presiding over a period of rapid growth of that institution. Walker was also elected president of the American Statistical Association (ASA) in 1882 and was drafted by the "new generation" economists to became the first president of the American Economic Association (AEA) in 1885. (from 1947, the AEA would award the "Walker Medal" every two years, to prominent economists for their lifetime achievements; this was discontinued after 1977, with the advent of the Nobel Memorial prize.)

Throughout his life, Walker strove to establish the "scientific" status of economics, and was a pioneer in using statistical data to illustrate economic arguments. While not really a "Neoclassical" in the strict sense, Walker nonetheless helped bury Classical economics by his 1875 demolition of the "Wages Fund" doctrine. This was followed up in his 1876 book, The Wages Question. Walker went on to develop a unique theory of distribution, which generalized the Ricardian theory of rent to explain the returns to labor, capital and entrepreneurship - -- thereby presaging the marginal productivity theory of distribution. Walker posited his new theory in an 1887 article in the QJE and challenged critics to tear it down. This led to a series of polemics in the QJE of 1887-90 with Silas MacVane, Sidney Webb and others taking up the gauntlet.

Avidly courted by both by both American Neoclassicals and the American Institutionalists, Walker cannot readily be classified as either. Being the son of Amasa Walker, Francis Walker was also particularly interested in currency questions, authored a well-received textbook on money, and became a proponent of bimetallism. But Walker also grew increasingly conservative with age. He eventually became an outspoken apologist of the Gilded Age and a formidable opponent of Henry George, socialists, populists and immigration.

|

Major works of Francis A. Walker

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Francis A. Walker Contemporary

Modern

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca