| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

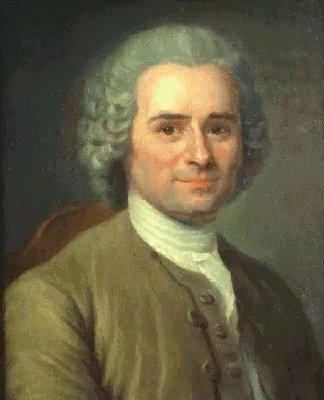

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1712-1778.

Swiss musician, writer and political philosopher of the Enlightenment era.

The details of Rousseau's life are well-known (if a bit embellished) from his Confessions. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a native citizen of the Republic of Geneva. His mother died in childbirth and he was initially raised by his father Isaac, a watchmaker of Calvinist faith, and an aunt. After an idyllic early childhood, Rousseau was suddenly orphaned at ten (more-or-less - his father ran off to Istanbul and was never heard from again). Rousseau stayed with relatives until he was apprenticed to an engraver, who treated him cruelly. In early 1728, at the age of sixteen, Rousseau finally ran away from Geneva and wandered around. He eventually made his way to Annecy (in Savoy, then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont), where he was taken in by the Madame de Warens, a bored provincial lady who apparently made it her mission to convert wandering Calvinist boys to Catholicism. She dispatched him to a Catholic hospice in Turin for religious instruction - and once he converted to Catholicism, Rousseau was duly given twenty francs and sent on his way. His conversion implied losing his Genevan citizenship.

Rousseau briefly found work as a servant for a lady in Turin for a spell, but was soon fired for stealing. A local Savoyard curate took pity on the young vagabond and found him a place in another noble family, but Rousseau set off wandering again, and was soon back in Annecy with the Madame de Warens in the Fall of 1729. She arranged for his music instruction - which quickly became a great passion for Rousseau. But more youthful escapades soon followed. In April, 1730, Rousseau was sent with his tutor on a mission to Lyons by the Madame de Warens. But along the way, Rousseau decided to give his tutor the slip and proceeded to go rambling around by himself. He went through a new set of adventures - gave a concert at Lausanne, hooked up with a Greek confidence man, was nearly arrested in Bern, escaped with the help of a French diplomat, etc. Around 1733, Rousseau finally returned to Annecy and the care of Madame de Warens. She now took Rousseau on as a lover, and arranged a bit of a living as her secretary and a music tutor. Eventually, in late 1735, tiring of being just a plaything, Rousseau persuaded de Warens to set him up in a isolated rustic cottage at Charmettes near Chambéry. There he sat down with piles of classics and scientific books, and finally began to acquire his only real education. The solitary idyll in the country cottage came to an end a few years later, in 1741, when Rousseau was hired by a local noble as a tutor for his son (the young Abbé de Mably).

After a year of commendable service in the Mably household, Rousseau moved to Paris in 1742, armed with letters of introduction, hoping to peddle a new system of musical notation he had invented to the Paris Conservatory and the Académie des Sciences (he failed). Rousseau found employment as the secretary to the Comte de Montaigu, the French ambassador to Venice, and traveled with him to Italy. Rousseau was in Venice for only a little while before he quarreled with his employer and was fired. Rousseau had to flee Venice to avoid arrest. The details of this affair are murky, but significant. Apparently the Comte swindled Rousseau out of some money, and Rousseau would spend years trying to get it repaid. His own friends in high places showed little sympathy for his case against the ambassador and suggested he drop the matter. Apparently, the experience embittered Rousseau greatly, and fed his growing hostility towards the French noble elite that would later find an outlet in his writings.

After leaving Venice, Rousseau returned to Paris to attend to his principal passion, music composition. His first effort, the operatic ballet Les Muses Galantes (written 1743 and produced privately) fell flat. It was during this time (c.1745) that Rousseau picked up a poor mistress, Thérèse de Levasseur, an illiterate servant maid who would remain his companion for the rest of his life (Rousseau would abandon their five children to foundling homes; he only got around to marrying her 23 years later - in 1768).

Rousseau's musical merits gave him entry as secretary and tutor into the Dupin household in 1745. Through the Dupins, Rousseau quickly fell into the philosophes circle - Diderot, Voltaire, d'Alembert, etc. - and reconnected with his former pupil Mably and his brilliant younger brother, Etienne de Condillac. Diderot and d'Alembert recruited Rousseau to contribute many fine articles on music to their Encyclopédie, which started to appear in 1749. Rousseau also wrote the article on "Économie" for the fifth volume (1755), but it was little more than a hack job. Rousseau eventually go to know the Physiocrats themselves (Quesnay, Mirabeau, Turgot, etc.), although he was apparently not very enthused by them.

Although music was his principal vocation, Jean-Jacques Rousseau's claim to fame is as a political and social philosopher. His first effort was his fiery Discourse on Arts & Sciences (1750), written as a submission to a competition at the Academy of Dijon. According to Rousseau, he was on his way to visit Diderot in prison in Vincennes in October 1749, when he came across a prospectus for the competition in the Mercure magazine. Rousseau claimed he developed his entire philosophical vision and system of thought en route to Vincennes ("I beheld the universe and became another man", Conf., Bk. 8, p.228). To the Dijon Academy's question - "Whether the reestablishment of the sciences and the arts has contributed to purifying morals" - Rousseau's answer was "no". Intellectual and scientific progress, Rousseau declared, has only encouraged moral corruption and the decline of civic virtue. The Discourse won the Academy's prize in August 1750, and went on to be published. Rousseau's challenge to the Enlightenment's central conviction - faith in progress - provoked a debate, and there was a lively engagement and interchange with his critics in the course of 1751. The success encouraged Rousseau to leave the employ of the Dupin family in Paris in 1751 and strike out on his own, eking out a living as a music copyist, a profession he would maintain for the remainder of his life.

Rousseau found further success with his small comic opera Le Devin de Village, which was played before King Louis XV at Fontainebleau in June 1752 (a contemporary parody of the opera, Bastien and Bastienne, would be later re-composed by Mozart in 1768). Inexplicably, Rousseau turned down the offer of a royal pension from the amused king. The Devin would go on to be well-received at the Paris Opera in March, 1753, but that same November Rousseau fell into polemics with his Lettre on French music. Rousseau waded into an intense debate in music circles on the relative importance of melody and harmony. Rousseau lauded the superiority of Italian over French opera (the latter represented by French composer Rameau). French musicians did not take it kindly, and Rousseau would be burned in effigy by the orchestra of the Paris Opera.

Tiring of France, Rousseau returned to Switzerland in 1754, resumed his Calvinist faith and re-acquired Genevan citizenship. During this time, Rousseau wrote his second Discourse on Inequality, for another competition held by the Dijon Academy. It would not win the prize this time, but Rousseau went ahead and had it published in April, 1755. It would be the more significant of the two discourses. The second discourse elaborated on Rousseau's famous vision of the state of nature and natural man, the "noble savage". Rousseau envisions man in his natural state to be inherently calm, humble and pacific (not necessarily moral, merely torpid and dull). Rousseau identifies the invention of private property as the moment of transformation. Private property introduces inequality in wealth, social distinction, hierarchy, power and eventually leads to the creation of the State. As a consequence, man becomes transformed into a social being, and his personal character is deformed - he becomes snobbish, heartless, immoral and violent, i.e. "civilized". Rousseau's thesis on inequality, now considered a milestone of the Enlightenment, raised eyebrows in philosophical circles, both inside France and abroad (the young Adam Smith took notice of it in his Edinburgh Review in 1755 (July, p.130)).

Rousseau returned to France in 1756 and in April, deciding to live closer to nature, moved to the small country house of L'Hermitage in the valley of Montmorency (a few miles north of Paris), offered by the Parisian salon mistress Madame d'Epinay. There, Rousseau sat down to sift through the manuscripts of the late Abbé de Saint-Pierre. But around this time Rousseau also got into conflicts with the philosophes, quarreling with Diderot, d'Alembert, Grimm and finally d'Epinay herself. In 1757, Rousseau broke with the philosophes, and moved to another house (Montlouis, also in Montmorency). This was among the more productive periods of his life, where he composed the bulk of his next few works. In the interim, Rousseau provoked the theatrical world with his Letter to d'Alembert (1758) denouncing the theater as a corrupting influence, severing individuals from their social milieu. He would return to Paris in 1759.

During his seclusion in the French countryside, Rousseau wrote his famous epistolary romantic novel, La Nouvelle Heloise, which was published in early 1761. Its title invokes the Medieval story of Abelard and Heloise, set in rural villages around Lake Geneva. It is a story of the forbidden love affair between a middle-class tutor Saint-Preux and his aristocratic pupil Julie, their forced separation, and Julie's marriage to Wolmar, a practical nobleman. The contrast between passion and reason, romance and social expectation, are among the themes Rousseau draws out in the novel. The novel was an immediate and massive success. It was unscrupulously pirated by publishers, and went on to become probably the best-selling novel of the 18th Century. Rousseau's novel had a profound influence on the literary scene in France, breaking the arid neoclassicism that had prevailed until then, and opening the new phase of romantic literature.

That same year (1761), Rousseau completed a tract on the origins of language that he had begun back in 1755 as a derivative of his second discourse. The French censor Malesherbes recommended it for publication, but Rousseau had two other works he wanted to put out first. The essay on language would end up unpublished in his lifetime.

Emboldened by the success of his novel, Rousseau published two new books in the Spring of 1762 that would change his fate. The first book was Du Contrat Social (April, 1762), Rousseau's most systematic political opus, following up on his second discourse . The famous opening phrase of its first chapter - "Man in born free, and is everywhere in chains" - can be justly regarded as a synopsis of Rousseauvian philosophy. Through the tract, Rousseau ranged against divine right, articulated the doctrine of the popular sovereignty, with governments as merely servants of the general will. The second book, published a month later (May, 1762), was Émile, ou de l’éducation, deriding the corrupting influence of human agency ("All is good when it leaves the hands of the Creator, all degenerates in the hands of man") and outlines a system of education for children that would allow the flourishing of "natural man". This drew a firestorm. He got in trouble primarily for a passage in the latter, known as the "Creed of a Savoyard Priest", on revealed religion, which was perceived as articulating the Socinian heresy (unitarianism). Rousseau was condemned both by the Catholic authorities in Paris (June 9) and the Calvinist authorities in Geneva (June 19). Orders were issued for Rousseau's arrest and his books were burned throughout France and Switzerland.

Rousseau fled France in the nick of time - initially to the domains of the canton of Berne in Switzerland. But the Bernese authorities quickly expelled him. In July 1762, the hunted Rousseau finally found refuge in Môtiers, in the canton of Neuchâtel, then ruled by Frederick II the Great of Prussia. Shortly after arriving, Rousseau wrote his Letter to Beaumont, answering the censure of Christophe de Beaumont, Archbishop of Paris. Rousseau would remain exiled in Moitiers for the next three years. Rousseau renounced his Genevan citizenship in 1763.

In November 1764, while ensconced in his Neuchatel haven, Rousseau wrote his polemical Letters from the Mountain, a passionate defense of his social contract, in response to a Swiss critic Jean Robert Tronchin, a member of Geneva's oligarchic council. The fury of Rousseau's tract, attacking the political legitimacy of the Genevan government, was shocking and drew more enemies. Even the hitherto-sympathetic Voltaire felt compelled to join ranks against him, and published a pamphlet on it (in the course of which Voltaire publicly revealed how Rousseau had abandoned his own children). Reaping the whirlwind, Moitiers was soon not safe anymore. In September 1765, a local pastor preached a fiery sermon against Rousseau, and a mob of his parishioners stoned Rousseau's house in Moitiers. Shaken, Rousseau moved to the apparent safety of the Island of Saint-Pierre in the Lake of Bienne. But the island lay within the jurisdiction of Berne, and the Bernese authorities ordered his expulsion again. In late October, 1765, Rousseau left Switzerland and made his way to Strasbourg, uncertain of where to go next. He received invitations from various well-wishers - Frederick II invited him to Potsdam, publisher Michel Rey invited him to Amsterdam, Pasquale Paoli invited him to Corsica and David Hume invited him to England. Rousseau decided to take up Hume's offer.

Through the efforts of some friends in high places, Rousseau managed to secure safe-passage through France, and would spend a couple of weeks in Paris in December 1765, hosted by Louis François, Prince of Conti. His stay in Paris was brief but eventful. His old enemies of the philosophes clique (mainly Encyclopedistes D'Holbach, d'Alembert, Diderot, Grimm, etc.) engaged in raillery at his expense, and tried to intrigue with the arriving Hume. English playwright Horace Walpole, then in Paris, authored a notorious fake letter, pretending to be Frederick II of Prussia, satirizing Rousseau's fear of persecution, which was soon circulating among chuckling readers in Paris and London [repr. in MacDonald].

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, accompanied by David Hume and a merchant De Luze, arrived in England on January 13, 1766. Rousseau initially moved into a house in west London. But two months later, on March 22, against Hume's advice, Rousseau left London and moved to a country estate in Wootton (rural Staffordshire), offered by a local gentleman Richard Davenport, an English fan of Rousseau's works (Rousseau and Hume would not meet again in person). It is at Wootton that Rousseau began writing his "Confessions".

Rousseau's bitterness and paranoia eventually wore down David Hume, and they soon had a falling out.. While away in the English countryside, Rousseau had instructed Hume in London to manage his incoming mail, and forward him only the important letters. But when articles critical of Rousseau appeared in the British press, the paranoid Rousseau began suspected Hume was their unnamed source. When the scurrilous Walpole letter was published in London in the St. James's Chronicle (Apr 1), owned by William Straham (a publisher friend of Hume's), Rousseau chided the Scottish philosopher for not standing up for him. A series of testy exchanges between Rousseau and Hume followed in June, culminating in a furious letter from Rousseau (July 10, 1766, repr), unloading his griefs against Hume, accusing him (among other things) of tampering with his mail and leaking its contents to the press. The quarrel got wider as Rousseau and Hume wrote to their circle of friends (both in Britain and France), complaining about each other. Hearing that Rousseau was writing his "Confessions", Hume anticipated their quarrel would figure in it, and decided to set the record straight in advance. Urged by the French Enlightenment clique (D'Alembert,Turgot, etc.), always ready for intrigue, - and against Adam Smith's advice - David Hume decided to take the quarrel public, and published their correspondence, first in French in Paris (Oct) and then in English (Nov). The Hume-Rousseau quarrel would become a sensation throughout Enlightenment circles in Europe, with other figures chiming in with their own take on it.

Rousseau decided not to reply to Hume, and instead arranged to leave England. Rousseau arrived in France on May 22, 1767 under an assumed name ("Jean-Joseph Renou"). But it fooled nobody - shortly after his arrival, he was received with a public banquet in Amiens. Rousseau initially took up an offer of refuge at the chateau of Fleury (near Meudon, southwest suburbs of Paris), hosted by Victor Riquetti (Marquis de Mirabeau), who hoped to convert the celebrity writer to Physiocracy (Lavergne, p.338). Mirabeau had Rousseau read Mercier de la Riviere's recent tract, Ordre naturel, but Rousseau found it tiresome and regarded the Physiocratic embrace of legal despotism off-putting. Extracting himself from his obnoxious host, Rousseau subsequently (June 21) moved to the more rural Chateau de La Trye (north of Paris), offered him by Louis François, Prince of Conti. From La Trye, Rousseau completed and published his Dictionary of Music, which he had been working on for years.

Technically still a fugitive, Rousseau descended deeper into paranoia. Rousseau left La Trye a year later (June 1768), going on to Lyons. He moved thereafter to Bourgoin (in the Dauphiné), where Rousseau finally officially married his long-suffering companion, Thérèse Levasseur (August, 1768). In January 1769 they moved to Grenoble, where Rousseau resumed work on his "Confessions". In April 1770, they returned to Lyons, where Rousseau's dramatized poem Pygmalion was given a public performance. Rousseau finally moved back to Paris in June, 1770 - returning to the city he had fled in 1762. He would remain in Paris, living in poverty as a music copier, for the last eight years of his life.

Rousseau's Confessions were completed by November 1770, but he decided to delay publication. Instead, over the next six months, Rousseau gave public readings of his text to gatherings around Paris. The affronted Madame d'Epinay, who figured large in the memoirs, used her connections to have the Paris chief of police shut them down in May 1771 and forbid further readings.

By that time, Rousseau was deeply engaged in another project, Considerations on the government of Poland, his last political tract, begun in October 1770 and completed around June 1771. Although tailored for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, some of it it applied to government generally. Curiously, Rousseau backed away from the direct democracy implied by the Social Contract and now advocated the merits of a representative system, with frequent elections. He found the Polish Senate too powerful, and recommended them being reduced and/or appointed by the Diet. Overall, finding the country too extensive, Rousseau recommends breaking up Poland into a collection of small self-governing cantons (in whatever local form - monarchical, democratic, etc., so long as the citizens "know each other"). But Rousseau's tract was still unpublished when Poland was overwhelmed by war and partition in early 1772, rendering its recommendations mute. It would only be published posthumously.

With his Confessions confined in cold storage by police order, Rousseau still felt a need to find a way to salvage his reputation. In 1772, Rousseau began a second autobiographical work, Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques, in the form of three dialogues, defending himself from his critics. Wandering and disorganized, the dialogues evince signs of mental breakdown from the impoverished and sick Rousseau. Completed in February 1776, the mentally distraught Rousseau attempted to deposit the manuscript at the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris, only to find it barred by a gate. His paranoia at its apex, Rousseau refrained from publishing the dialogues, and instead entrusted copies to Etienne de Condillac and Brooke Boothby. Around this time, Rousseau's erstwhile protector, the Prince of Conti, died (August 2), and with him (Rousseau imagined) all remaining hopes for rehabilitation. In the aftermath (September 1776), Rousseau began his third autobiographical work, Reveries of a Solitary Walker, the most introspective of his works. He would not live to complete it.

At the invitation of the nobleman Stanislas de Girardin, Rousseau left Paris in April 1778 to stay in Ermenonville, hoping to recover his health. Jean-Jacques Rousseau died in Ermenonville on July 2, 1778. There were rumors after his death that he had committed suicide or was poisoned by his enemies, but none of that was ever substantiated. Rousseau's remains, originally entombed in a lake island in Ermenonville, were moved to the Pantheon in Paris in 1794.

Rousseau's posthumous works began to appear shortly after his death. Boothby arranged for the publication of Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques in 1780. The first part of the Confessions, along with the Reveries, were published in 1782, the second part of the Confessions were published in 1789. The publication of the Confessions revived public interest in Rousseau, and new editions of his collected writings began to put out by publishers, ensuring widespread familiarity with his works on the eve of the French Revolution in 1789.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau's political writings had enormous impact - most immediately during the French Revolution, during which his name and ideas were invoked repeatedly. Rousseau's work would also inspire numerous socialist writers and movements of the 19th Century.

Rousseau's impact on economics is more elusive. Jean-Jacques Rousseau made only one explicit contribution to economics: the article "Économie" in the fifth volume (1755) of the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert (later reprinted as a Discourse on Political Economy). The article contains no obvious economic theory and is merely a pre-taste of the political philosophy he was to lay out in his Social Contract (1762). His earlier polemical Discourse on Inequality (1754) - which argued that civilization had destroyed man's "natural goodness" and that the invention of private property was the source of all social, political and economic inequality - had some impact on economics, and is prescient of later Marxian doctrines.

However little direct influence, Rousseau's work nonetheless had a substantial indirect impact on economics. In particular, Rousseau initiated (or certainly promoted) among his fellow Enlightenment philosophers the intellectual artifact of a "natural state" of society. This extended to social equilibrium and lent itself to "natural value" concepts which were very much ingrained in the thinking of the Physiocrats and Adam Smith. His appeal to this state via his "natural man", the "noble savage", is reminiscent of the analogies formed in modern economics (think of Robinson Crusoe).

However, Rousseau did not push that idea as an analogy to the existing world - as so many economists did and still do. Rather, a thorough pessimist about existing human society, Rousseau recognized that this "natural state" was perverted by "civilization" and that the appetites and motivations of civilized man had been consequently corrupted and constructed by his interaction with society, making him also ancestral to Institutionalists.

Rousseau's principal drawback - and the one focused on by his critics - was his lack of specificity. Rousseau does not locate it in historical circumstance - he jumps from state of nature to civilization in one leap, where others (e.g. Scottish writers and later Historicists and Marxians) preferred gradual evolutionary stages, embedded in actual history. He also has little practical political advice to give - the state of nature is unrecoverable, property exists, civilization exists and he lays out no blueprint for their abolition. One can only emulate what was lost, e.g. in education and in political systems, as far as possible. But in the 1790s French Revolutionary radicals (and English ones, such as William Godwin) saw a manifesto for wholesale political and social reform to bring the "natural state" about. In its ultimate manifestation, they envisioned not Hobbes's "equilibrium" of competing wants, but rather a collective state with extra-personal dedication to a "General Will". Only in such a state, as per Rousseau's assertions, could the true "natural man" re-emerge and be truly free. It is these last observations that make Rousseau the putative father of Socialism (utopian and otherwise).

|

Major Works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Jean-Jacques Rousseau Pseudo-Rousseau

Contemporary works on and in reply to Rousseau

Modern

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca