| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

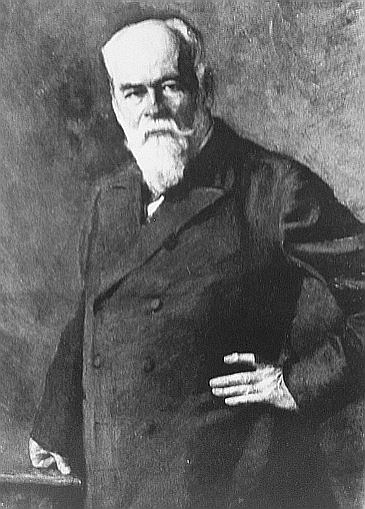

Gustav von Schmoller, 1838-1917.

German economist at the University of Berlin, paramount leader of the Younger German Historical School

Gustav von Schmoller was born in Heilbronn, then part of the Kingdom of Württemberg, the son of a military officer and administrator of royal estates. While still young, Schmoller worked alongside his father in the Württemberg bureaucracy. He studied cameralistics and law at the University of Tübingen, obtaining his degree in 1861. Following his family footsteps, Schmoller joined the Württemberg statistical bureau, although he was forced to resign two years later, apparently because of his pro-Prussian views.

Schmoller never submitted a separate Habilitation thesis; his gold-medaled doctoral thesis on the economic impact of the Reformation, plus his 100-page article digesting the statistics of the 1861 Zollverein census of Württemberg (1862) was considered enough to secure him an appointment as an assistant professor at the Prussian University of Halle in 1864. The very next year, Schmoller was promoted to full professor of political science (Staatswissenschaft), taking the chair of the retiring Eiselen, who had taught Prussian administration, law and economics at Halle. As he later reported, Schmoller was unfamiliar with Prussia, and delved into detailed historical research of it. He became particularly intrigued in the examination of the reforms of Friedrich Wilhelm I (the oft-ignored father of Frederick the Great).

In 1872, Schmoller left Halle to occupy a newly-endowed chair at the University of Strasbourg, which had just been transformed from a French into a German university, after the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871. It was there that Schmoller crossed paths with Georg F. Knapp. That same year (1872), at the instigation of Berlin professor Adolph Wagner, Schmoller organized the Eisenach conference on the "Social Question" (Sociale Frage) that led to the formation of the Verein für Sozialpolitik, ("Society for Social Policy"), a group of economists which supported a kind of corporatist state-industry-labor nexus. German liberals deplored the Verein's advocacy for state interventionism and came to label Schmoller and the Historicists as Kathedersozialisten (or "Socialists of the Chair") - a jestful appellation they never entirely lived down. Schmoller's profile was raised in a polemical debate with Heinrich von Treitschke on the question of social reform (1874)

In 1878, Schmoller launched the Staats- und Sozialwissenschaftliche Forschungen, a paper series of studies conducted by his own students. In 1881, Schmoller took over the editorship of the journal Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich from Brentano and Hotzendorff and thereafter the JfGVV would often be simply referred to as "Schmollers Jahrbuch".

In 1882, Gustav von Schmoller was appointed professor at the powerful University of Berlin, the flagship university of the new German Reich, succeeding to the chair of Adolf Held. In 1884, Schmoller became a member of the Prussian Staatsrath, and in 1887 a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.

German Historicism was resurrected under Gustav von Schmoller, who, from his throne at the University of Berlin, had a domineering influence in the German academic world in the latter quarter of the 19th Century. Schmoller's attacks on Classical and Neoclassical theory were more vociferous than his predecessors, such as Roscher, had dared essay -- almost rejecting theory as such, not merely its pretensions to universalism. As a result, Schmoller deplored the older Historicists' penchant for "stages" theories of history and their attempt to provide a "positive" as opposed to "normative" theory of economic history. Much of the work undertaken or commissioned by Schmoller was directed largely to microscopic analysis of political and economic history. Schmoller would himself insist that he did not oppose theory , but merely that "knowledge of facts" preceded theory, and that the collection of facts was currently insufficient to inform and construct theory.

Schmoller's opposition to Neoclassical economic theory entered him into a famous methodological debate (Methodenstreit) with Carl Menger in 1883-84. Some argue that Schmoller lost the debate by the simple fact of non-engagement (it is reported that upon receiving Menger's Investigations, he returned it unread to its author and published a "semi-review" of it claiming that it had not even been worth reading). Nonetheless, it is also alleged that Schmoller used his considerable influence on the German university appointment system to kept Classical and Neoclassical economic theory largely out of German teaching - earning him the eternal enmity of Menger's Austrian School in Vienna. Schmoller's legacy in economics has been tainted by the fact that one of the most prominent recorders of the history of economic thought - Joseph Schumpeter - was himself an Austrian with little sympathy for the Historical School.

In the meantime, actual Socialists and Marxians regarded Schmoller's group (Adolph Wagner notwithstanding) as an instrument of government and businesses to control and mollify the working classes. This was virtually confirmed time and time again when the Verein would come up with patchy justifications for the industrial policies of Bismarck. The Verein rarely opposed an economic policy decision by the Imperial German government.

A small anecdote from Pareto: At a conference in Geneva where Pareto was presenting a paper, Gustav von Schmoller was in the audience and kept noisily interrupting Pareto's talk by shouting "There are no laws in economics!" The next day, when Pareto spotted Schmoller in the streets of Geneva. Pareto approached Schmoller and hid his face, pretending to be a beggar (which was not too difficult since Pareto was a shabby dresser). "Please, Sir," Pareto said, "Can you tell me where I can find a restaurant where you can eat for nothing?" Schmoller replied, "My dear man, there are no such restaurants, but there is a place around the corner where you can have a good meal very cheaply." "Ah," said Pareto triumphantly, unveiling himself, "so there are laws in economics!"

Schmoller's main works are his study on the weavers guild of Strasbourg (1879) which was followed up by further studies the guilds in 17th C. and 18th C. Brandenburg-Prussia. His posthumous 1922 history of towns is also considered a classic. Schmoller's most characteristic work is probably his 1898 Umrisse, a history of Prussian financial and trade policy, which clearly expresese his ideas about the process of formation of the national economy. Schmoller emphasized the vital importance of a powerful, centralizing Prussian state in breaking-up local particularlisms that were hindering economic development and social justice. Schmoller regarded the authoritarian Prussian state as the only force capable of implementing social reforms beneficial to workers (e.g. 1918). Schmoller's major work is arguably his Grundriss der allgemeinen Volkswirtschaftslehre (1900-04), although it is not as characteristic of his Historicist and polemical views as some of his smaller works.

|

Major works of Gustav von Schmoller

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Schmoller

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca