| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

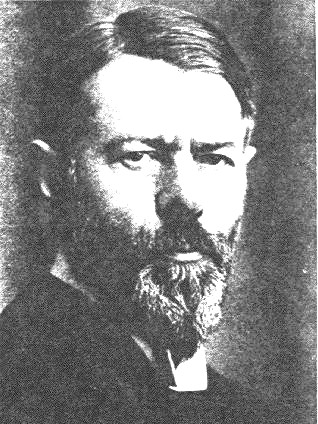

Max Weber, 1864-1920

Max Weber is best known as one of the leading scholars and founders of modern sociology, but Weber also accomplished much economic work in the style of the "youngest" German Historical School. He is the older brother of location theorist Alfred Weber.

Weber's family was an old Protestant family originally from the Catholic ecclesiastical state of Salzburg which, but had moved to Bielefeld (in northern German) because of counter-reformation efforts by the Archbishop of Salzburg. While Max's uncle retained the family manufacturing firm in Bielefeld, his father, Max Weber Sr, pursued a professional career as a magistrate in Erfurt. Max Sr. would later become a politician, serving as a deputy of the conservative National Liberal Party in the Prussian Diet in the 1870s. Max's mother was a devout Calvinist. Max Weber studied law and agrarian history at the University of Heidelberg and then Berlin. He produced two dissertations - one in law (on commercial law in medieval Italy) and one on history (on the agrarian Roman history). Weber married his second cousin, Marianne, in 1893. He was appointed professor of economics at Freiburg in 1895, but moved the next year to a chair in political science at Heidelberg in 1896, succeeding Karl Knies. However, in 1897 Weber suffered a mental breakdown (shortly after the death of his authoritarian father) which left him essentially incapacitated for the next five years. He recovered and returned to Heidelberg in 1902.

After a trip to the United States in 1904 (to attend the St. Louis World's Fair), and upon his return worked on his Protestant Ethic. Shortly after, Weber struck up an affair with former student Else von Richthofen, who also happened to be the wife of his colleague, the economist Edgar Jaffé (Else later went on to become the paramour of his brother, Alfred Weber). Max Weber followed up on his work with series of studies of world religions, writing on Confucianism and Taoism (1913), on Hinduism and Buddhism (1916) and on Judaism (1917-19), eventually published in 1920-21. Through the latter part of his life, Weber worked on his magnum opus, Economy and Society, which he began in 1914, but it remained unfinished upon his death in 1920.

Although Max Weber and Werner Sombart are often lumped together as part of that generation in German economics, no two men could be less alike. The superficial, fanciful and Kaiser-worshipping Sombart was nothing like the thorough, rational and Kaiser-despising Weber. Nonetheless, while Weber was not completely immune from German nationalism, he was just not the military-imperial jingoist Sombart was. Weber firmly believed that the Herrenvolk should circumscribe their ambitions.

That personal attitude was reflected in his most famous economic work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905, initially published as articles in the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik). In it, Weber argued that the presumed anti-capitalist Puritanical rhetoric of eschewing earthly acquisitiveness was actually an impetus for that very acquisitiveness. The thesis was novel and well-known. Catholicism, Weber argues, was tolerant towards the acquisition of earthly gain and winked at lavish expenditure, an idea engendered by hierarchical structure of the Church (which required struggling and jockeying for "position") as well as its own tradition of lavish expenditure (the church) and its oft-used earthly powers of forgiveness for sin. This might make one conclude that the Catholic ethic was more predisposed towards capitalism than the Protestant (as others, before and since, have argued).

But no, replied Weber. It is true that the Protestant doctrines asked men to accept a humbler station and concentrate on mundane tasks and duties and, without a hierarchical church structure, there was no example of upward-mobility, acquisitiveness and expenditure. Yet it was precisely this that engendered the "work-and-save" ethic that gave rise to capitalism. Dedication to and pride in one's work, Weber claimed, is inevitably a highly productive attitude. The Lutheran mandate of worldly calling, reinforced by the Calvinist doctrine of predestination, changed practical ethics and made the rise of capitalism possible. The Protestant ethic of "godliness" through the humble dedication to one's beruf (calling/duty/task), meant economic productivity was consequently higher in Protestant communities. By contrast, prior Catholic ethics saw work as merely a means to an end - to consume. Once one's material needs were met, work was set aside and one dedicated one's self to other, higher pursuits. The upward-mobility that was possible in hierarchical Catholic society meant that a lot of people found themselves in jobs which they saw only as way-stations to higher and better positions - thereby dedicating only a minimal or nominal attention to the given task as finding it either beneath their dignity or certainly not worth resigning to as their end in life. Consequently, Weber concluded, Catholic communities tended to be less productive.

The higher productivity of Protestant communities was coupled with higher thriftiness. The sinfulness of expenditure and lavish display of earthly goods was a notable Protestant pietist principle. So too was it Catholic, but the Catholic Church had been more prepared to forgive these (and other) sins. The Protestant church had no such power and thus the inducement to the faithful to stay modest in consumption was high. Yet the higher productivity of the Protestant essentially meant that they earned more than the Catholic, and yet because they saved more, they essentially accumulated; the Catholic was less productive but spent more.

Thus, Weber concluded, the idea of "capitalist accumulation" was born directly out of the Protestant ethic - not because the Protestant churches and doctrines condoned acquisitiveness as such (often quite the contrary), but rather quite inadvertently through its claim to productive dedication to beruf and thriftiness. The subsequent ethical "legitimization" of capitalist acquisitiveness in later society under the rubric of "greed is good" was simply a distorted statement of what was already a fact. In no sense, claimed Weber, is the capitalist ethic of "greed" the creator of "capitalist society" (however much it might later be a propagator), but, rather, quite the opposite.

Weber's 1905 thesis (echoed independently by R.H. Tawney) was naturally quickly disputed and has since been more or less discredited as a "complete" theory of the rise of the capitalism. In particular, the empirical assertion associating Protestantism with prosperity and Catholicism with otherwise, was disputable. But the more significant aspect was its timing. The Protestant reformation occurred in the 16th Century, while the capitalist system only came to fruition in the 19th Century. This challenged the Marxian theory of historical materialism, that asserted ideas emerged from economic conditions. Weber seemed to be arguing the opposite, that the ideas associated with capitalism - accumulation as an ethical imperative, rationalism as a world view - preceded the economic system by centuries, and emerged quite independently of it, from religious doctrines. Weber did not quite establish a rigid causality, he did not claim the ideas caused the economic system in some deterministic Hegelian fashion. Rather, Weber preferred to assert that Protestant ideas facilitated the emergence of capitalism. He leaves room for real economic facts causing the rise of capitalism. But these material facts only bore their transformative fruit in a ground where practical ethics had been previously transformed by religious ideas. Weber uses the Goethean term "elective affinity" ("Wahlverwandtschaften", p.54), sometimes translated as "correlations", to describe the relationship between ideas and the material system reinforcing each other. While the material basis for the emergence of capitalism existed in other societies before, in Catholic Renaissance Italy or Confucian China, religious ethics did not facilitate or reinforce its growth.

Weber's other main contributions to economics (as well as to social sciences in general) was his work on methodology. There are two aspects to this: his theory of Verstehen, or "Interpretative" Sociology and his theory of positivism. His Verstehen doctrine is as well-known as it is controversial and debated. His main thesis is that social, economic and historical research can never be fully inductive or descriptive as one must/should/does always approach it with a conceptual apparatus. This apparatus Weber identified as the "Ideal Type". The idea was essentially this: to try to understand a particular economic or social phenomena, one must "interpret" the actions of its participants and not only describe them. But interpretation poses us a problem for we cannot know it other than by trying to classify behavior as belonging to some prior "Ideal Type". Weber gave us four categories of "Ideal Types" of behavior: zweckrational (rational means to rational ends), wertrational (rational means to irrational ends), affektual (guided by emotion) and traditional (guided by custom or habit).

Weber admitted employing "Ideal Types" was an abstraction but claimed it was nonetheless essential if one were to understand any particular social phenomena for, unlike physical phenomena, it involved human behavior which must be understood/interpreted by ideal types. Economists prick up your ears - for here is the methodological justification for the assumption of "rational economic man"!

Weber's work on positivism or rather his controversial belief in "value-free" social science, is also still debated. While his arguments in this respect were not novel, they did signal a complete and forceful break with Schmoller and the "Young" Historical School.

Weber's other contributions to economics were several: these include a (seriously researched) economic history of Roman agrarian society (his 1891 habilitiation), his work on the dual roles of idealism and materialism in the history of capitalism in his Economy and Society (1914), present Weber on his anti-Marxian run. Finally, his thoroughly researched General Economic History (1923) is perhaps the Historical School at its empirical best.

Max Weber's position as an economist has been debated, and indeed, it is generally accepted now that it is in sociology that his impact was greatest. However, he comes at the end of the "Youngest" German Historical School where no such distinctions really existed and thus must be seen as an economist in that light.

|

Major Works of Max Weber

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Max Weber

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca