| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

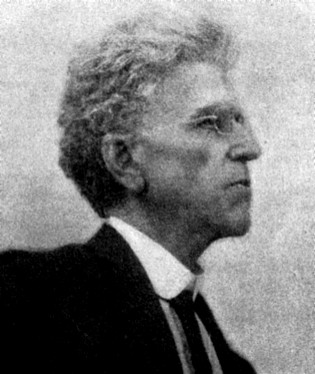

Herbert J. Davenport, 1861-1931.

Herbert Joseph Davenport, a rather unique specimen, served as the glue between two other highly original American thinkers: Thorstein Veblen, whom Davenport deified, and Frank H. Knight, who deified Davenport.

Born in Burlington, Vermont, Herbert J. Davenport studied at South Dakota, Harvard, Leipzig and Paris before finally obtaining his doctorate under Laughlin and Veblen at Chicago in 1898. After a couple of years as a high school principal in Lincoln, Nebraska, Davenport took up an appointment at Chicago in 1900, working alongside his old masters. After Veblen's departure in 1906, Daveport found the atmosphere at Chicago stultifying, and led him to take up an offer from the University of Missouri in 1908. He finally settled down at Cornell University in 1916.

Although accepting Veblen's work on the heterogeneous psychological underpinnings of economic behavior, Davenport nonetheless eschewed the Institutionalist approach. Instead, Davenport articulated a curious mix of Austrian and Lausanne economics supported on Veblenian pillars. Davenport's approach was perhaps only shared by his Cornell colleague, Frank A. Fetter - who liked to group Veblen, himself and Davenport together into what he called the "American Psychological School". However, the true inheritor of Davenport was his student, Frank Knight, whose own peculiar brand of economics exhibits the Davenport stamp throughout.

In Davenport's view, the Austrian theory of alternative cost was essentially correct, but the rest of the marginalist theory of value was based on faulty psychological underpinnings. There is not, in Davenport's view, a single, universal principle governing economic behavior - for lack of an alternative, marginal utility might do as an analytical device for a single individual, but one inevitably ends up in convoluted nonsense when trying to extend that across individuals into markets or societies.

Furthermore, he resented the ethical implications often drawn out by contemporary economists in terms like "maximum utility", "efficiency", "productivity" and "wealth". Provocatively, Davenport considered all things which are produced and marketed, be they burgler's tools, murder weapons or obscene literature, to be "wealth" and activities such as pickpocketing, cheating and the slave trade to be "productive" (his examples!).

Davenport rejected the tripartite division of factors of production - arguing that labor and land were produced means of production and thus shared the same features as "capital". Interest, however, was for him a monetary phenomenon and, in his view, financial imbalances were the precipitators of economic fluctuations. These fluctuations might also not be self-righting, and thus government intervention might be called for. Thus, as Knight would note later, "Davenport was a forerunner of Keynes. In certain paragraphs, one cannot tell whether reading Keynes or not." (Knight, 1942 as quoted in Patinkin, 1973).

The central player in the economic field was, for Davenport, the entrepreneur, as is made evident in his most original work, Economics of Enterprise (1913). However, his contributions can also be traced out his hard-going 1896 textbook - which, for the time, was far more theoretical than most - and in his damning critiques of Classical and Neoclassical (esp. Marshall's) theory in his 1908 and 1935 books.

Not a man to pull his punches, Davenport's sardonic language could out-Veblenize Veblen's own. "A bold fellow of Scottish descent, with style formed on Carlyle", is how Alvin Johnson described him.

|

Major Works of Herbert J. Davenport

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Herbert Davenport

|

All rights reserved, Gonšalo L. Fonseca