| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

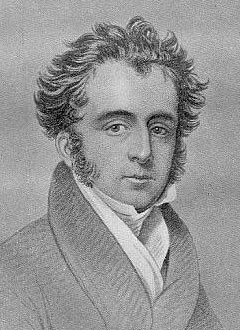

George Grote, 1794-1871

English banker, classical historian and utilitarian reformer.

Scion of an Anglo-Dutch (via Bremen) banking family, George Grote's aspirations to a classical education were terminated by his father, who set him up on a career in his banking house of Prescott & Grote in London. It was almost inevitable that the young banker encountered David Ricardo, who turned him towards political economy and introduced him into the circle of James Mill and Jeremy Bentham, and developed a life-long friendship with the young John Stuart Mill. Grote was a founding member of the Political Economy Club (1821).

George Grote embraced the utilitarian project and kicked into print with a vigorous promotion of the extension of suffrage (dependent on education) and parliamentary reform (1821). Immediately afterwards, Grote was charged with editing Bentham's 1770s writings against the 'natural religion' theory into a new treatise under a pseudonym (1822; the proportion of the result that was Bentham's and that which was Grote's is unclear). Around 1823, Grote turned his Threadneedle St. home to a utilitarian reading room for the himself, the Mills and their friends.

Alongside his banking job and utilitarian projects, George Grote was moving deep into classical history of ancient Greece, a endeavor his own inclination, prodded by James Mill's own hellenophilia. In 1826, he published a large article in the Westminster Review, that demonstrated his researches were well on their way.

In 1826, Grote got deeply involved in the founding of University College London (UCL). In this task, his role would be ambiguous. Although his tireless work helped the university launch, his radical anti-clericalism would lead to trouble. In 1830, Grote broke with his utilitarian friends - Brougham, James Mill and even Bentham - over the appointment of John Hoppus as professor of logic and philosophy of mind at UCL. Grote's opposition was grounded on the fact that Hoppus was an ordained congregationalist minister, and thus unsuitable for the job at a non-denominational school.

In 1830, as parliamentary reform approached, Grote entered into public debates again and, in 1832, was elected to parliament himself. He would serve until 1842.

After leaving parliament, Grote resigned from his bank and embarked on a European tour, during which he deepened his historical researchers. They would eventually culminate into his magisterial multi-volume magnum opus, the History of Greece, that would begin to appear in 1846.

In 1849, Grote seemingly buried the hatchet and was elected to the UCL council. But he would soon cause trouble again. In 1866, Hoppus's resignation had opened the chair in philosophy, and the bulk of the electors opted for James Martineau, the professor of philosophy at Manchester New College and, as chance would have it, an ordained unitarian minister. Again Grote's anti-clericalism hit high gear and he launched a highly-public opposition to Martineau's appointment. Grote won the day, securing the chair for the inexperienced George Croom-Robertson (a friend of John Stuart Mill). UCL's leading professor, Augustus de Morgan, resigned in protest. Jacob Waley, the exiting professor of political economy, also lodged a public complaint.

Despite all this, Grote succeeded Henry Brougham as president of the Council of UCL in 1868. Grote's only significant contributions to utilitarian philosophy proper are contained in his posthumously-published Fragments (1876).

|

Major Works of George Grote

|

|

HET

|

|

Resources on George Grote

|

All rights reserved, Gonšalo L. Fonseca