| Profile | Major Works | Resources |

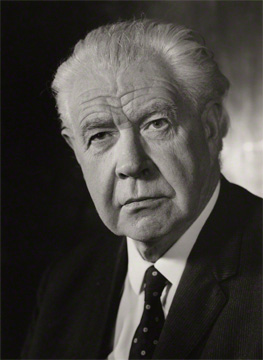

Lord Lionel C. Robbins, 1898-1984.

Lionel Charles Robbins was a peculiar Englishman in the economics world of the 1920s for a very simple reason: he was not a Marshallian but rather a follower of Jevons and Wicksteed. However odd, what really made him downwright unique in Britain was that he had actually read the Continental European economists - Walras, Pareto, Böhm-Bawerk, Wieser and Wicksell. As a result of his Jevonian-Lausanne-Austrian- Swedish infections, Lord Robbins was instrumental in shifting the train of English economics off its Marshallian rails and onto Continental ones.

Robbins's tools were the London School of Economics and a famous1932 Essay on economic methodology. Succeeding at a young age to the unfortunate Allyn Young to the chair of the L.S.E. in 1929, the thirty-year old Robbins proceeded quickly. Among his first appointments was Friedrich A. von Hayek. Robbins and Hayek presided over the "golden age" of the L.S.E. in the 1930s, breeding a new generation of "English-speaking continentals" such as Hicks, Lerner, Kaldor, and Scitovsky.

Robbins's early essays were very combative in spirit, stressing the subjectivist theory of value beyond what Anglo-Saxon economics had been used to. Robbins's famous work on costs (1930, 1934) helped bring Wieser's "alternative cost" theorem of supply to England (which was opposed to Marshall's "real cost" theory of supply). His critique of the Marshallian theory of the representative firm (1928), and his critique of the Pigouvian Welfare Economics (1932, 1938), helped put an end to the Marshallian empire -- aided and abetted (and occasionally thwarted) every step of the way by his kindred spirit across the pond, Frank Knight.

It was his 1932 Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science where Robbins made his Continental credentials clear. Redefining the scope of economics to be "the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between scarce means which have alternative uses" (Robbins, 1932). His defense of a priori theory and attack on Marshallian intuitionism is reminiscent of von Mises's essay.

Robbins was initially opposed to Keynes's General Theory. Robbins's 1934 treatise on the Great Depression is an exemplary Neoclassical analysis of that period. Indeed, Robbins always saw his L.S.E. as a bulwark against Cambridge, whether it was populated by Marshallians or Keynesians. However, Robbins was eventually to recant and reconcile with the Keynesian Revolution (1947).

In the latter part of his life, Robbins turned to the history of economic thought and policy, publishing various classic studies on English doctrinal history (1952, 1958, 1968, 1970, 1976). Although the ascendancy of the L.S.E. is foremost among his legacies, Robbins is also greatly responsible for the modern British university system - having advocated its massive expansion in the 1960s.

|

Major works of Lionel Robbins

|

HET

|

|

Resources on Lord Robbins

|

All rights reserved, Gonçalo L. Fonseca