| School | Troops | Resources |

The Italian Tradition

Up until recently, Italian economists did not figure very prominently in histories of economic thought. Most English-speaking economists would probably only be able to name the giants Vilfredo Pareto and Piero Sraffa (both of whom were emigrants, incidentally). But Italy has had a very old and distinctive heritage in economics that is impossible to ignore.

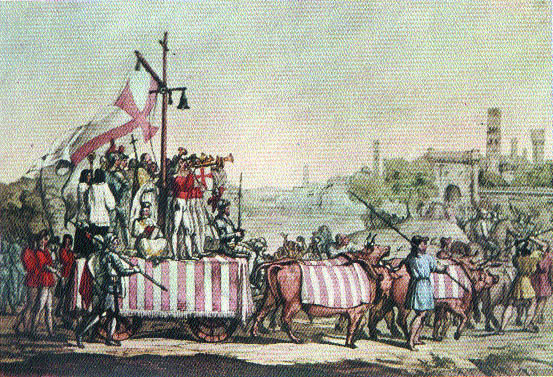

Italian writers generally figure prominently in the Scholastic era, of course, and the Renaissance. Many of their early works were handbooks to guide governance - some from the heights of religious or humanist idealism, like Matteo Palmieri, others grounded in the more hard-nosed realities of a commercially-minded society, like Machiavelli and Carafa. Still others tried to maintain the connection between idealism and practice - such as Botero on governance, Davanzati on money, or Stracca on commercial law. Perhaps most famous was Antonio Serra's Breve Tratatto (1613), considered by many to be the first great treatise on political economy.

In the 18th Century, the Neapolitan economist, Ferdinando Galiani (1751) "broke off" from the main streams of Enlightenment economic thinking. He rejected the path of the French Physiocratic and Scottish schools and defended Mercantilist policies, but with a twist. Galiani initiated the two avenues which formed the "Italian tradition" in economics: the serious analysis of government as an economic entity and a utility-based theory of natural value.

For Galiani, the economy must be analyzed more juridically than pseudo-scientifically. Government, he argued, is an important entity in any economy. It can, via its laws and fiscal policies, influence the economy and society for good and evil. Theories of the "natural state" without a State were, for him, hopelessly abstract and dangerously naive. The policy conclusions of the Physiocratic sect -- laissez-faire, laissez-passer -- were a consequence of their having excluded the State by assumption. Galiani's line of reasoning was closer to the French Neo-Colbertistes and German Neo-Cameralists.

Galiani also argued that the "cost" theories of value which the Physiocrats embraced were plain wrong. In his view, natural value arises from utility-based demand interacting with the scarcity of supply -- an argument already anticipated by another Italian, Bernardo Davanzati. This idea was developed in parallel in France by men like Abbé Condillac, Jacques Turgot and others.

British Classical economics made its way to Italy in the 19th C. Sometime expatriates, like Giovanni Arrivabene brought acquaintance with the Belgian-French liberal school. During this period, the leading figure was doubtlessly Francesco Ferrara, at the time professor in Turin. It was Ferrara who spearheaded the creation of the Societą di Economia Politica in 1852, composed mostly of Piedmontese economists and liberal political figures - the society's first president was Camillo Cavour. But after Italian unification in 1861, and Ferrara's semi-retirement into politics, the focus of activity moved to Florence, the new capital. In the 1850s and 1860s, Ferrara also put out the Biblioteca dell' Economista, a series of Italian translations of classical economic works from Britain and France, which was helped popularize economics in Italy.

On the initiative of Francesco Protonotari, editor of the influential literary journal Nuova Antologia, a new national association, the "Societą di Economia Politica Italiana" was launched at a conference in Florence (June 1868). Originally intended as a professional association of emerging professional economists, it soon devolved, as its predecessor had, into a policy shop-talk, exposing the fissures between Italian liberals and a new crop of more interventionist Italian economists inspired by the German Historical School (the Italian historicists got the appellation the "Lombard-Venetian school" - bestowed upon them by Ferrara - as its most prominent professors taught at Pavia and Padua). Alarmed at the rise of the historicists, Francesco Ferrara published a polemical article in the Nuova Antologia (Aug 1874) denouncing the Lombard-Venetian historicists as "Germanizers", Socialists and spoilers of Italian youth . Ferrara encouraged fellow liberals to found the "Societą Adamo Smith" in Florence (Sep 1874), and a journal, L'Economista, committed to the defense of classical liberal principles and against the state interventionism advocated by the historicists. In the meantime, Lombard-Venetian historicists responded with a circular letter, known as the "Padua manifesto" (dated Sep 11, 1874), signed by Luigi Cossa, Antonio Scialoja, Fedele Lampertico, and Luigi Luzzatti, articulating the principles of the new historicist school and calling on a conference to discuss social reform. The Padua circular was subscribed by numerous young Italian economists, At their congress in Milan in January 1875, the Lombard-Venetian historicists formed the "Associazone per il Progresso degli Studi Economici" (modeled on the German Verein) and went on to found a new economics journal, the Giornale degli economisti (GdE) later that same year (April 1875).

Around this time, the Italian politician and sometime economist Quintinio Sella got into the mix by persuading the prestigious Reale Accademia dei Lincei in Rome (of which he was president since 1874) to set up a section on "Moral, Historical and Philological Science", which included a space for political economy.. Four economists were appointed to the Accademia dei Lincei - Antonio Scialoja, Fedele Lampertico, Angelo Messedaglia and Luigi Luzzatti - all of them of the Lombard-Venetian school, three of them authors of the Padua manifesto. To balance things out a bit, Ferrara became a member of the Lincei in 1876, but simultaneously the German historicist Wilhelm Roscher was invited as a foreign honorary member.

The methodenstreit between the liberal "Tuscan" school and the historicist "Lombard-Venetian" school drove a split in Italian economists that dragged on through the 1870s. Nonetheless, both societies, and their journals, were relatively short-lived. Like the societies before them, they quickly descended into the political realm and served up little academic fare, serving primarily as vehicles for policy debates on parliamentary bills..

By the time of the Marginalist Revolution, the Italians were not caught by surprise and contributed much to its early construction. Indeed, the bulk of the Lausanne School came from Italy -- Vilfredo Pareto, Enrico Barone, Giovanni Antonelli, Pasquale Boninsegni, Luigi Amoroso, etc. Some commentators, such as Henry Schultz, have preferred to call it simply the "Italian School". The influential Neoclassical economist Maffeo Pantaleoni, the Italian "Marshall", can be considered part of this group. The Giornale degli Economisti was re-launched by Pantaleoni in 1890, now as a mouthpiece of Neocassical liberalism.

The economic theory of the State was a more distinctively Italian concern and passed through several stages. In its earliest stage, it was explicitly utilitarian. Cesar Beccaria, and Pietro Verri focused their analysis on the impact of the State and fiscal policy on the economy. They viewed the state as an instrument to improve general social welfare (whether by engaging or disengaging from the economy; reshaping its laws and practices, etc.). The Italians found in the notion of utility - or "happiness" -- a criteria by which to evaluate policy. Specifically, they argued that social welfare was greatest when the society achieved the "greatest happiness of the greatest number", which was to become the formula of utilitarian social policy.

However, the utilitarian perspective still held the state as a "benevolent despot". In the late 19th Century, the "Italian Fiscalist School" developed a different approach. Beginning with the work of Francesco Ferrara, and following through Pantaleoni, Antonio de Viti de Marco, Ugo Mazzola, Luigi Einaudi and others (including, notably, Pareto and Barone), the State began being analyzed as an economic entity itself. This involved examining the government as both a "productive" agent (i.e. a producer of collective goods -- which are also inputs into private production) as well as an "optimizing" agent (i.e. a "revenue-maximizer"). They were particularly keen on analyzing the impact of fiscal policy in this context. The Italian "fiscal science" continued on its distinctive path through the second half of the 20th Century. James Buchanan credits the Italian fiscalist school as the intellectual precursors to the "public choice" school.

The third distinctive strain of Italian economics has been the remarkable "Classical" Neo-Ricardian counter-revolution initiated in 1960 by Piero Sraffa. Although most of the early action was at Cambridge, the Neo-Ricardian school took root in Italy as Sraffa's Italian students, such as Pasinetti and Garegnani, returned home. There it was not only tolerated but even attained a degree of respectability that seemed impossible anywhere else.

|

The Renaissance Italians

The First Economists

The Italian Enlightenment and Utilitarians

Italian Classicals

The Lombard-Venetian School (Italian historicists)

The Lausanne School Italians

Italian Socialists

Italian Neo-Ricardians

Other Distinctive Italians

|

| HET |

|

Resources on the Italian Tradition

|

All rights reserved, Gonēalo L. Fonseca